Evolving evidence demands for Scotland’s climate change policy: Implications for knowledge brokerage

Research completed: August 2025

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7488/era/6857

Executive summary

Governments around the world are struggling with complex climate change policymaking and need clear evidence from researchers to make confident decisions in this highly uncertain area.

ClimateXChange (CXC) is the Scottish Government’s centre for expertise on climate change and one of the world’s first dedicated climate-focused knowledge brokers. This report reviews CXC research outputs between 2011 and 2024 to understand what types of climate evidence the Scottish Government has needed, how this has changed over time, and what this means for future work. It found that through this specific programme, policy-driven evidence demand has been dominated by mitigation, particularly in three sectors:

- energy

- agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU)

- buildings infrastructure

Demand for evidence in the energy sector has increased in volume and thematic focus. This includes a growing demand for energy system modelling, reflecting the need to anticipate supply and demand, and evaluate the system-wide impacts of decarbonisation measures. In the AFOLU sector, demand has focused most strongly on decarbonisation and carbon sequestration, especially peatland restoration. While the range of evidence demand has broadened over time, these two areas continue to dominate. Research on buildings and housing infrastructure is similarly focused on decarbonisation, energy efficient technologies and energy system modelling.

Unlike mitigation research – which often explores connections across multiple sectors –research on climate change impacts is more fragmented, with studies focusing on individual sectors and single hazard events rather than interconnections. Evidence requests for adaptation are similarly scattered. Although a slight trend towards the monitoring of adaptation actions is emerging, demand for adaptation research represents just a third of the outputs reviewed.

This review also finds that evidence-demand includes instrumental evidence – which directly informs policy decisions – and conceptual evidence, which helps policymakers better understand emerging or complex issues that may not have immediate policy applications but are crucial for long-term strategic thinking. However, demand has shifted from instrumental and conceptual evidence – drawing on scientifically well-established climate science and emerging evidence – towards anticipatory evidence. Anticipatory needs are particularly focused on understanding policy impacts, behavioural responses and public scrutiny.

This analysis explores the role of ClimateXChange (CXC), and shows that over time, government requests to CXC have shifted towards more interdisciplinary and transition-focused challenges. This shift presents new ways of working for knowledge brokers and an opportunity to broaden CXC’s reach across government.

This research offers policymakers a basis to reflect not only on how they use commissioned research in climate change policy, but also on the types of research they commission to inform policymaking.

Abbreviations

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CXC | ClimateXChange |

| SCCAP | Scottish Climate Change Adaptation Programme |

| SG | Scottish Government |

Introduction

In the face of escalating climate challenges, evidence-informed policymaking has become a cornerstone of effective climate governance (Tangney, 2022). Policymakers increasingly rely on research evidence to design and implement policies to support climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience building. However, the process of integrating evidence into actionable policies and strategies is complex and contingent upon a variety of factors that influence how evidence is produced, utilised, interpreted, and applied in the policymaking process (Juhola et al. 2024; Cvitanovic et al., 2025).

What is knowledge brokerage?

Knowledge brokers have long been understood as the link between producers and users of knowledge. Their roles range from supporting knowledge dissemination to driving the application of solutions (Scodanibbio et al., 2023). Traditional definitions of knowledge brokerage have largely been framed around a unidirectional transfer of evidence from academia to policymakers, emphasising a linear pathway of research findings into policy processes. However, contemporary perspectives increasingly recognise knowledge brokering as a dynamic and iterative practice (Tangney, 2022, Juhola et al., 2024, Turnhout et al., 2013). Rather than simply translating academic research outcomes, knowledge brokers also facilitate co-production processes, where knowledge products are collaboratively generated and contextualised within the governance, socio-economic and political landscape in which it is applied (Reinecke, 2015).

In the context of the climate crisis, where policymakers must respond to urgent and complex challenges, the role of knowledge brokers become increasingly crucial. Effective knowledge brokering also requires the ability to navigate complex environments, engage with diverse stakeholders, and mediate between competing values and priorities (Scodanibbio et al., 2023). Knowledge brokerage has thus evolved as a field of practice and is increasingly recognised as a critical area of analysis in policy studies (Cvitanovic et al., 2025, Juhola et al., 2024). Researchers have examined the roles, functions, and dynamics of knowledge brokers (Van Enst et al., 2017, Wreford et al., 2019), along with monitoring the contribution and impact of knowledge brokers on policy and decision-making (Maag et al., 2018).

While successful cases of knowledge brokering have been documented (Cvitanovic et al., 2025), some aspects of the knowledge brokering processes have not yet been explored, particularly concerning the temporality of evidence in climate policymaking. Climate change is driving widespread and disproportionately negative impacts, particularly for marginalised and disadvantaged populations. Given the rapidly narrowing window of opportunity to implement adaptation and mitigation measures at the necessary scales, there is an urgent need to examine how these temporal constraints have influenced the types of evidence demanded by policymakers. Key questions that have not been explored are: How have policymakers’ evidence needs evolved over time in response to shifting climate risks and policy priorities? To what extent has the urgency of climate actions shaped the way knowledge brokers produce, translate, and deliver evidence? Importantly, what does this reveal about the knowledge brokering as a dynamic and adaptive process, and how can knowledge brokers be better supported in the evolving landscape of evidence-informed policymaking?

The role of ClimateXChange (CXC) in knowledge brokerage and research rationale

To explore these questions, this study focuses on ClimateXChange (CXC), a science-policy boundary organisation or knowledge broker for climate change policymaking in Scotland. CXC was established in 2011, to serve as Scottish Government’s centre of expertise on climate change, providing policymakers with timely, relevant, and accessible evidence to support climate change policymaking. CXC’s inception was driven by the Climate Change Scotland Act (2009), a world leading policy that set ambitious emissions reduction targets and introduced requirements for regular policy planning and reporting (Nash, 2020). In response, CXC was established as a knowledge brokerage mechanism to bridge the gap between science and policy. It was designed to deliver targeted research that addresses critical climate policy questions while operating within the short decision-making timescales of government. CXC also provides rapid responses to pressing policy queries from Scottish Government’s policy teams.

CXC originally focused on evidence synthesis, translating scientific research into non-technical policy briefs that highlighted key insights for policymakers. Over time, its role has expanded beyond research synthesis, into a more collaborative approach. CXC now also works proactively to identify emerging policy needs, co-produce research projects with Scottish Government, and facilitate stakeholder-driven knowledge exchange (Wreford et al., 2019). This shift reflects a broader transformation in knowledge brokerage, moving from passive translation of research to active engagement in actively shaping the nature and direction of evidence requests from policymakers. Scotland, with its ambitious net zero by 2045 target, provides a compelling case study of evidence-informed policymaking, with CXC playing a central role in supporting this goal. A comprehensive review of research outputs produced by CXC reveals key trends in the evolving demands of evidence. By examining the research outputs or evidence base generated by CXC for the Scottish Government, we explore the evolving nature of evidence-based policymaking in Scotland. Understanding these dynamics is essential for strengthening evidence-informed policymaking. As climate risks intensify and policy priorities shift, often driven by government funding or political support, knowledge brokers are also expected to respond to the temporal shifts in the political landscape. Their ability to navigate varying levels of government support and evolving demands of policymakers significantly influence the way they broker knowledge. Analysing the evidence, co-created by knowledge brokers, provides insights into the evidence-based policymaking landscape.

In this report, we examine the research outputs commissioned through CXC and analyse their thematic focus and policy relevance. We then assess the policy-driven demand for evidence by the Scottish Government, characterising how evidence-based policymaking has evolved since 2011, when CXC was started. Instead of mapping specific evidence outputs and assessing their direct influence on Scottish policies and programmes, the focus of this report is on examining how the demand for research and evidence among climate policymakers has evolved over time. By analysing this shift, we aim to understand the broader trajectory of policy-research interaction.

CXC is funded by the Rural and Environment Science and Analytical Services Division (RESAS) of the Scottish Government and therefore it should be noted that it is one of five centres of expertise tasked with supporting the Scottish Government in evidence driven policymaking. The Scottish Government use a wide range of mechanisms to access relevant research evidence and CXC is one of these.

There are likely to be sectors and policy areas – that the Scottish Government has worked on and sought evidence for – which are missing from this review because they have been sourced elsewhere (e.g., across the wider Scottish Government Strategy Research Programme). The focus of this review was specifically research commissioned by CXC, rather than the broader range of evidence sought by the Scottish Government from other sources.

Methods

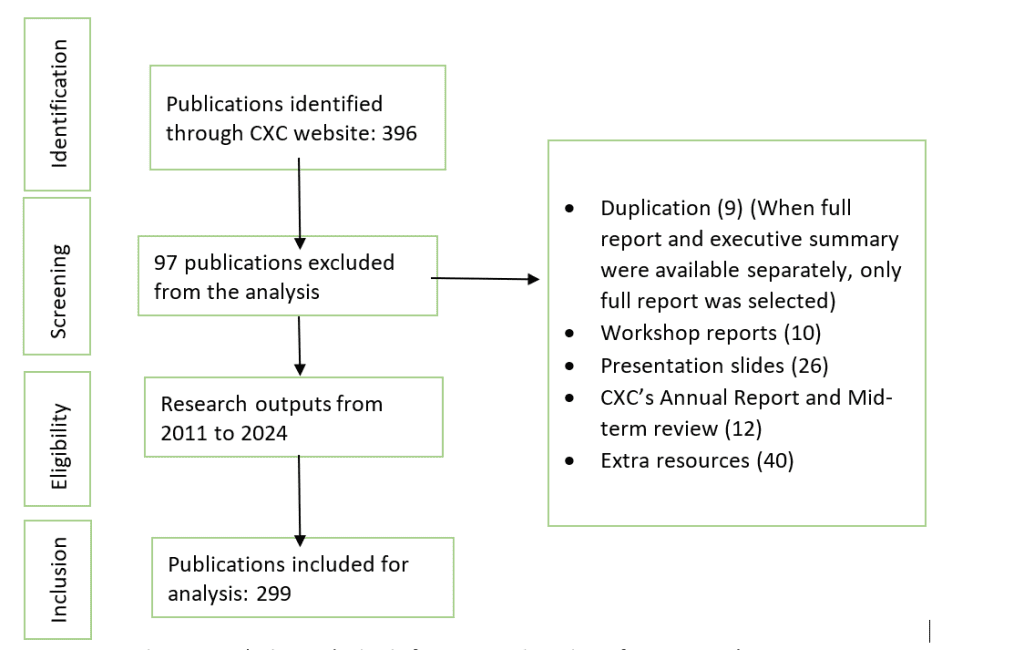

We mapped CXC publications along a timeline from 2011 to 2024. The publications were obtained from the publicly accessible CXC website and downloaded for analysis. The website hosts 396 publications, including a range of different outputs such as research publications, workshop reports, presentation slides, and meeting summaries. While these knowledge products highlight the range of different roles that CXC plays in the evidence-informed policymaking landscape, only research publications have been included for this review. The exclusion criteria for this review were defined to ensure a focus on research publications only.

The following types of documents were excluded (resulting in 299 publications included in our analysis):

- If both a full report, and its corresponding executive summary were available, the executive summary has been excluded.

- Publications that summarise the discussions or outcomes from workshops or meetings with Scottish Government or wider stakeholders, have been excluded. Presentations slides, either standalone or part of the research project, have also not been considered. Screening for these resulted in 45 publications being removed.

- CXC’s annual reports and mid-term reviews were not considered. This excluded 12 publications.

- Supplementary materials such as appendices for any research outputs have not been considered in the analysis. 40 publications that were considered extra resource were excluded.

Figure 1: Inclusion and criteria for systematic review of CXC research output

Publications were categorised based on the year the research was commissioned to reflect policy priorities at the time. When the commissioning and publication years differed, the commissioning year was used, as it best represents the policy window and demand for evidence. We mapped CXC publications chronologically along a timeline, categorising them based on whether they addressed climate change mitigation, adaptation, or impacts. Additionally, each publication was classified by sector and main thematic focus, and grouped according to shared themes (see Appendix A, B and C).

The classification of research projects was conducted using NVivo software based on three key criteria: the sector addressed by the research, the thematic focus of key terms associated with the project, and the policy goals it aimed to support. The policy goal refers to how the research project was framed in the publication and which of Scottish Government’s strategy or policy goals it considered. This could only be done by closely reading the text within the research publication, and considering the underlying motives (i.e., mitigation-driven or adaptation-driven) of the Scottish Government. We then analysed the text of the CXC reports to understand the demands being made, the responses delivered, and the emergent findings and themes – which were subsequently coded in NVivo. Additional to the topic analysis, two further areas were examined: the policy framing and the evolution of evidence asks.

Framing can be understood as the use of dominant narratives that shape both policy responses and research agenda. Policy framing allows policymakers to transition from descriptive assessments of climate change to prescriptive recommendations for actions, as different framing inherently suggest different policy responses and strategies interventions. Dewulf (2013) argues that by looking closely at how policymakers frame specific policy issues we can try to understand how particular interests are advocated for or undermined, and how particular actors or issues are included or excluded from policy debates. In the context of Scotland’s evidence-based policymaking, analysing the framing of research commissioned by the CXC for the Scottish Government provides insights into which policy areas receive attention, how policymakers define key challenges, and what type of policy actions are being pursued. The framing of research commissioned is discussed in Section 4.

In the analysis, we examined how Scottish Government’s evidence demands have emerged within the context of climate change policymaking.

Results

In this section, we used the timeline mapping (Appendix A, B and C) to create infographics that illustrate how evidence demands have evolved over time and highlight sectoral trends. We provide an overview of evidence demands from the Scottish Government across three thematic categories: mitigation, adaptation and climate change impacts.

Mitigation

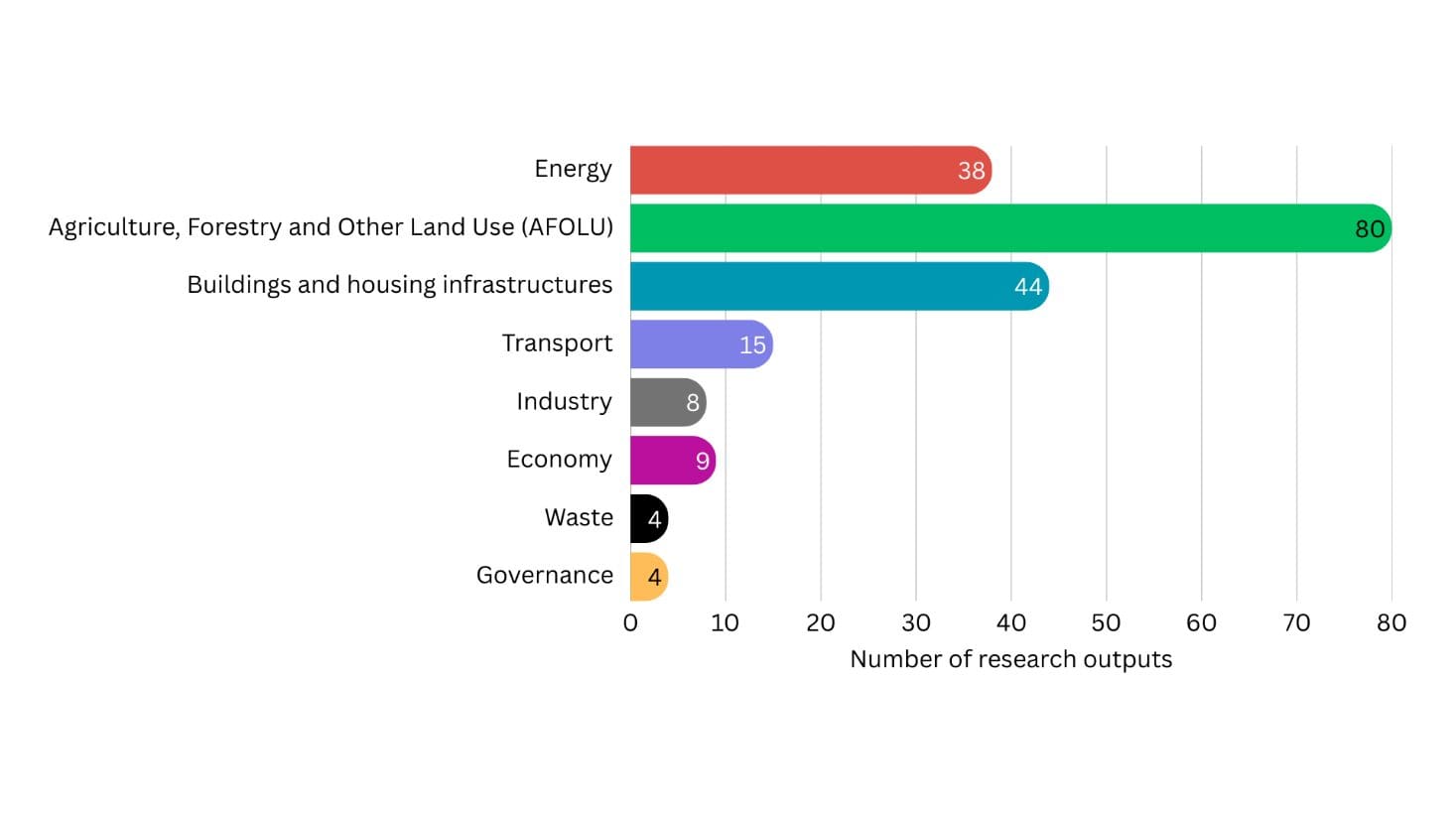

igure 2: Number of mitigation-related research outputs across key sectors

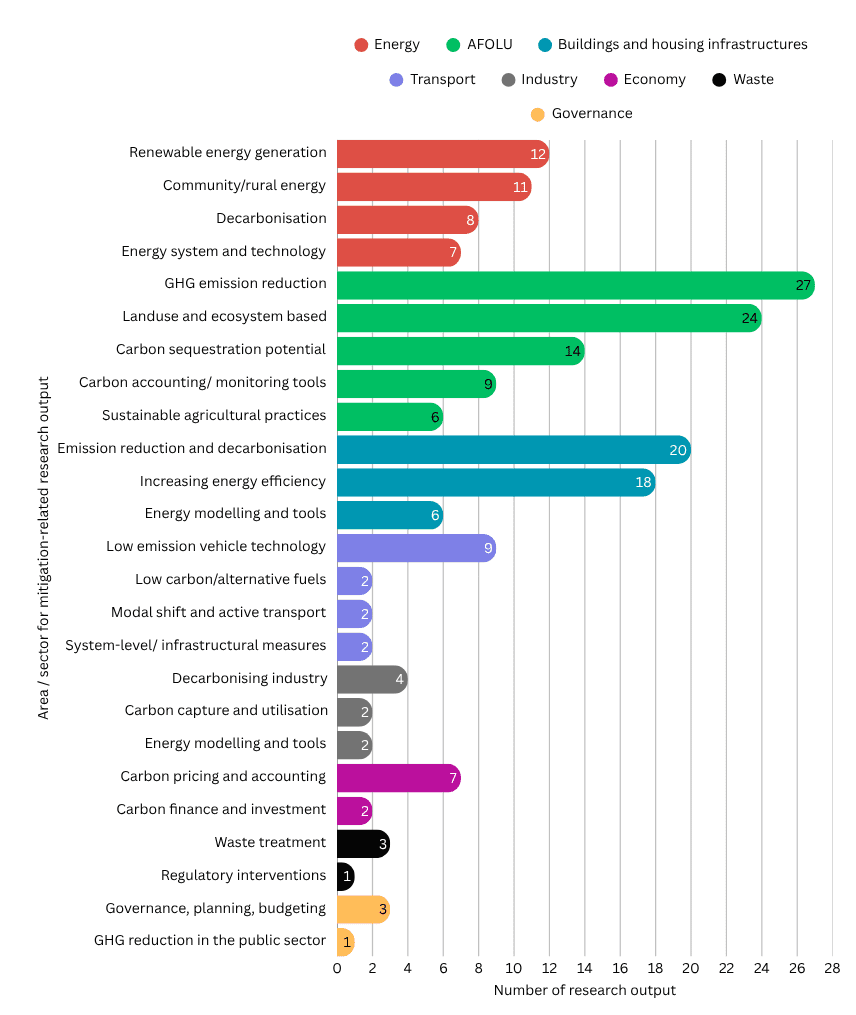

In Figure 3, Y-axis (vertical) represents specific mitigation-related research topics under broader sectors such as energy, land use, buildings and transport – which are distinguished by different colours. The X-axis (horizontal) shows the number of research outputs for each topic, indicating the amount of research activity or evidence demand.

Within mitigation, the evidence demands have been mostly for three sectors: energy, AFOLU, and building and housing infrastructure. AFOLU dominates the mitigation research demand with a combined 74 publications across emission reduction (27 outputs), ecosystem and land use approaches (24 outputs), sequestration (14 outputs), and carbon monitoring tools (9 outputs). There have been 44 research outputs for buildings and housing infrastructures, focusing on: decarbonisation (20 outputs), energy efficient technologies (18 outputs), and energy system modelling (6 outputs). Similarly, there have been 38 research outputs for the energy sector, with emphasis on renewable energy generation (12 outputs), decarbonisation and system-level transition. By comparison, mitigation-related research in the transport (15 outputs) and industry (8 outputs) sectors is relatively limited. Sectors such as waste (4 outputs), economy (9 outputs), and governance (4 outputs) have also received comparatively less attention.

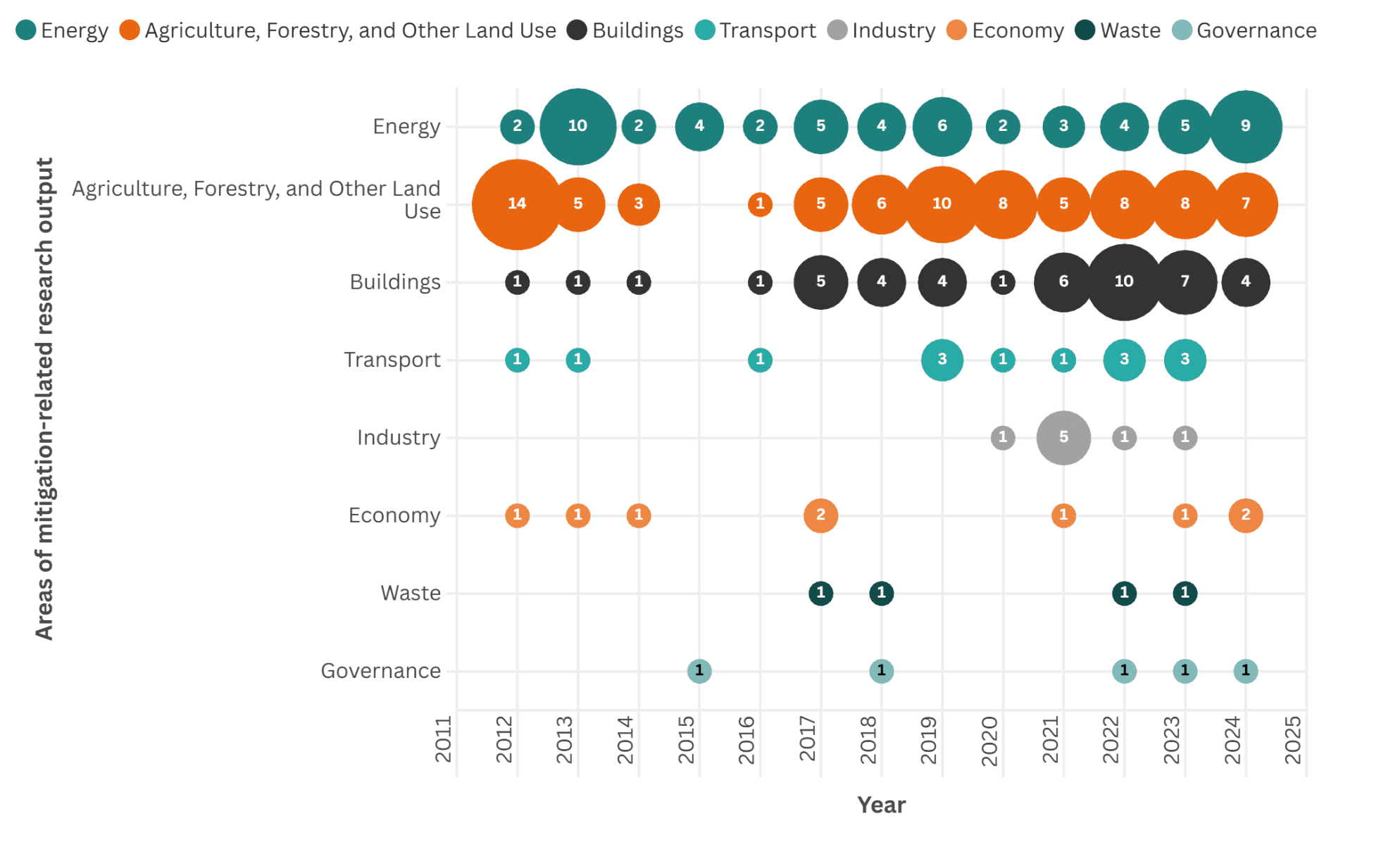

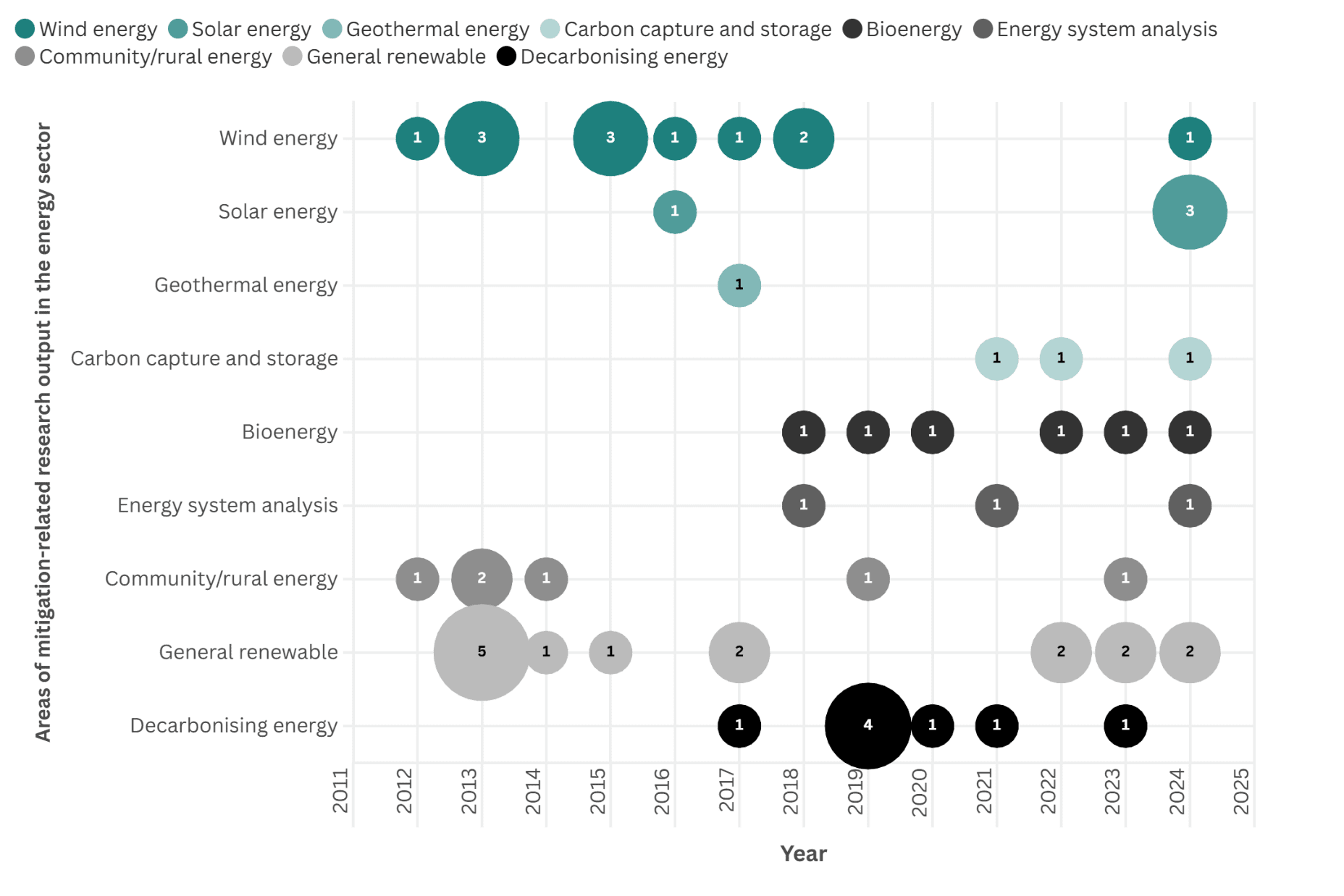

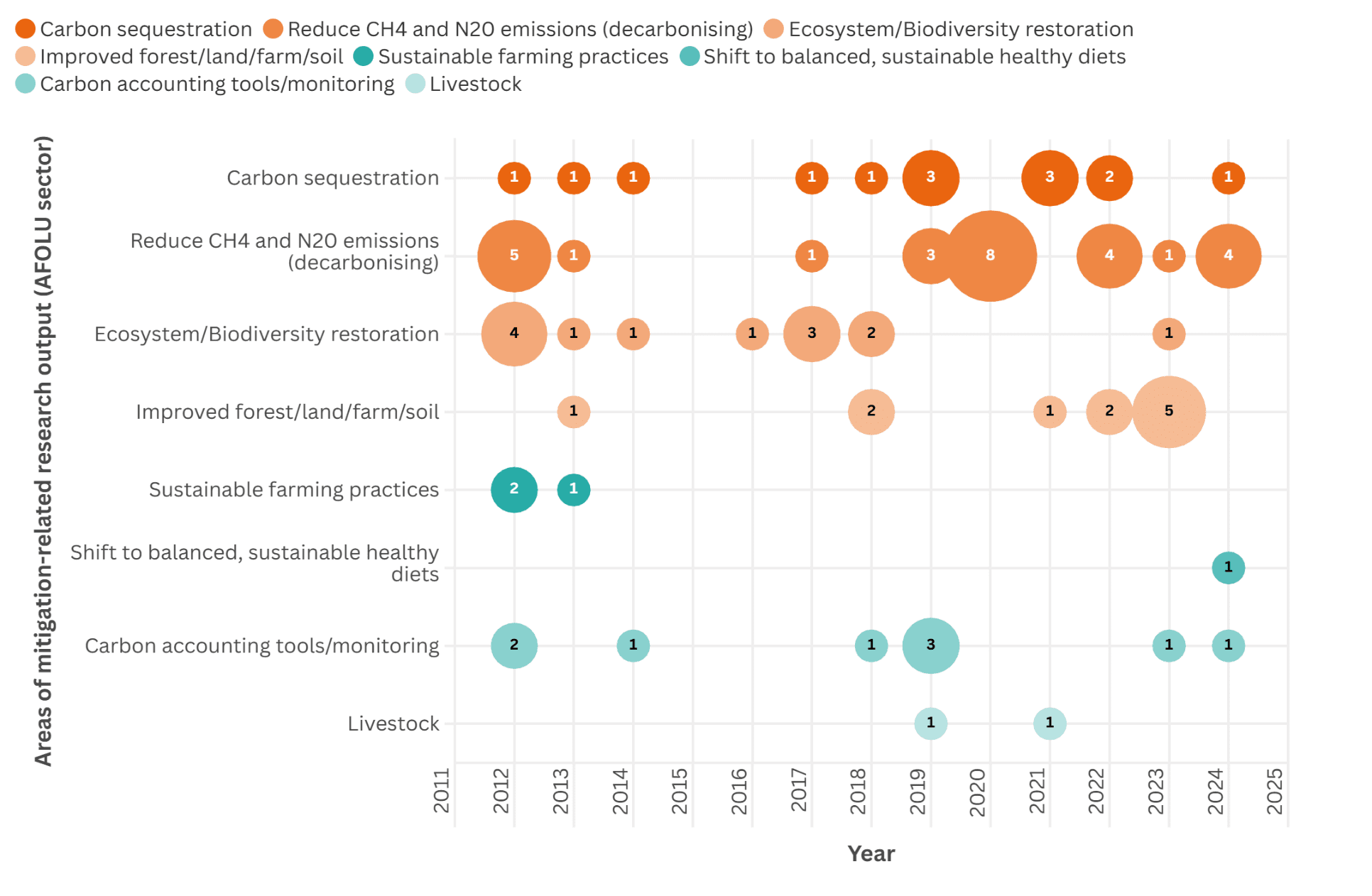

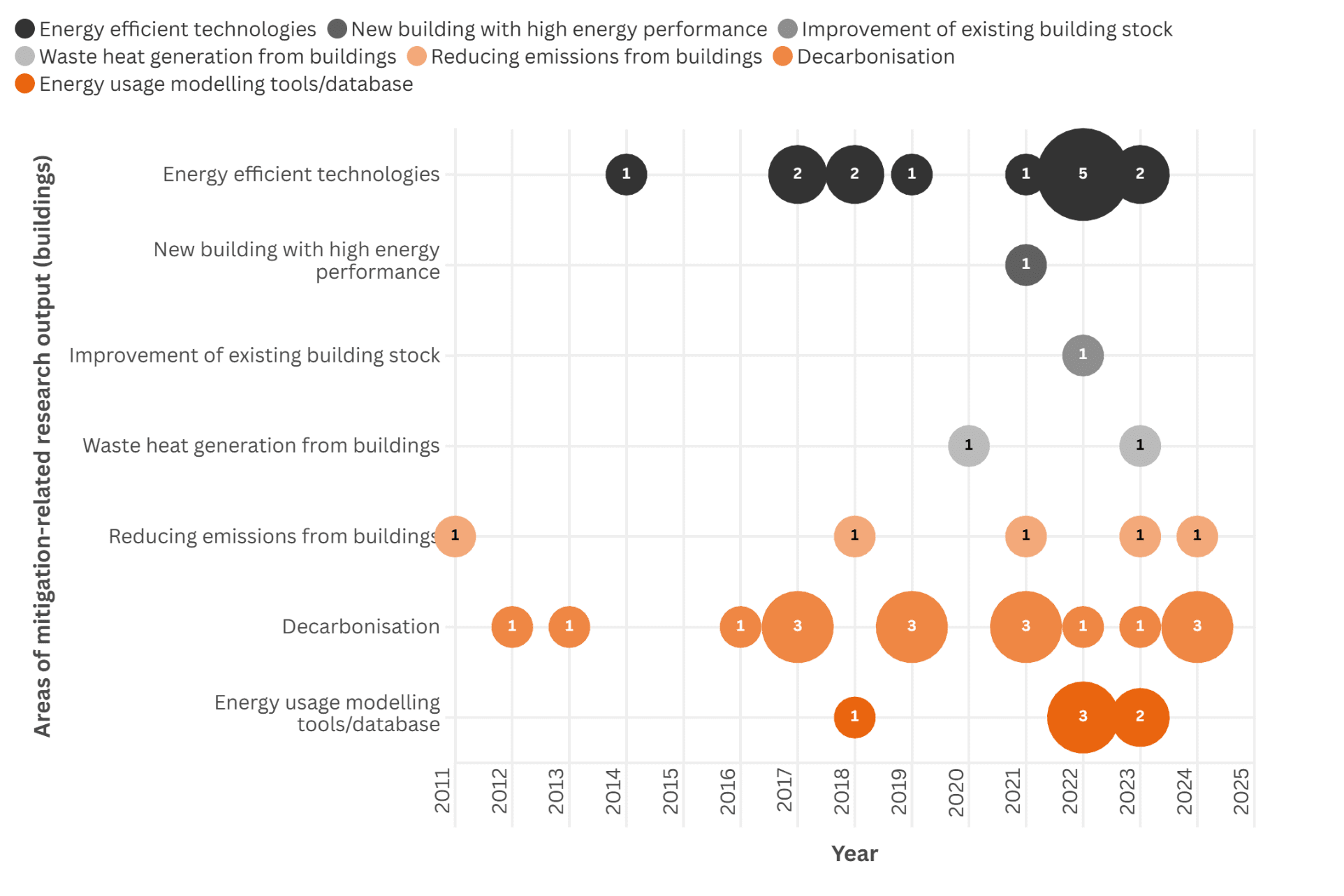

Figures 4, 5, and 6 are bubble charts that show mitigation-related research outputs across different sectors from 2012 to 2024. The x-axis shows time, the y-axis represents different sectors, and the bubble size reflects the number of research outputs for the given year. This representation allows us to see when the evidence demand was the highest, which sectors or themes drew most attention, and how evidence demand has shifted over time.

Figure 4 shows the number of mitigation-related research outputs across different sectors from 2011 to 2024. The highest and most consistent evidence demand has been for the AFOLU and the energy sector, which dominate throughout the period – with especially high volumes after 2017. This is not surprising given that funding and direction for CXC work has come from RESAS division within Scottish Government. Building and housing infrastructure emerged as another significant area of interest, particularly between 2017 and 2024. Other sectors like transport, industry, economy, waste, and governance received comparatively less focus.

Transport outputs appear sporadically, with small bubbles in most years and slightly higher activity after 2019. Within which, evidence demand on low emission vehicles and shipping is emerging and reflects a response to net zero goals. However, despite this emerging focus, the transport sector as a whole remains under explored by CXC research compared to its contribution to national emissions. According to the Scottish Greenhouse Gas Emissions Statistics for 2022, the transport sector emitted 12.9 MtCO₂e, making it the highest-emitting sector. In comparison, agriculture and buildings each emitted 7.7 MtCO₂e, while industry emitted 8.8 MtCO₂e (Scottish Government, 2024).

Industry features only a few contributions, with the highest evidence demand in 2021. Evidence demand on economy are scattered and remain small in scale. Waste and governance are marginal, with very limited activity appearing only in recent years.

A detailed breakdown of the theme within each sector is provided in Appendix A. The tables in the Appendix allow for a detailed evaluation of evidence demand across each sector, depending on the area of interest.

Figure 5 shows number of mitigation-related outputs in the energy sector, by different themes of mitigation-related output in the energy sector from 2012 to 2024. Over the years, evidence demand in the energy sector has increased both in number and thematic focus. This suggests a growing interest in a wide range of mitigation options.

There has been a strong and consistent demand for evidence about renewable energy generation. There has also been an increase in evidence demand on decarbonising energy since 2017. This shift is accompanied by a growing demand for energy system modelling, reflecting the need to anticipate supply and demand and evaluate the system-wide impacts of decarbonisation measures. Similarly, there has been low but consistent demand for evidence on Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) and bioenergy.

Figure 6 shows different themes of mitigation-related evidence demand within the AFOLU sector from 2011 to 2024. In the AFOLU sector, the highest demands have related to decarbonisation and carbon sequestration, particularly in regard to peatland restoration. While the spectrum of evidence demand has broadened over time, it continues to be dominated by these two areas.

There had been a noticeable evidence demand for ecosystem and biodiversity restoration between 2012 and 2018, but the evidence demand has decreased recently. There has been some demand for carbon accounting methodologies and tools for AFOLU. This suggests a demand for robust tools to quantify emissions and monitor progress, which is vital for both national and international obligations on reporting emissions. In contrast, there has been limited demand for evidence on livestock, and sustainable, healthy diets.

Figure 7 shows themes in mitigation-related evidence demand within the buildings and housing infrastructure sector. Demand in this sector has increased significantly in recent years, with decarbonisation emerging as the dominant focus. There has been evidence demand on emissions reduction in both domestic and non-domestic buildings, influenced by the proposed regulatory changes under the Heat in Buildings Bill. Since 2021, there has also been growing attention to energy-efficient technologies, accompanied by an increasing demand for energy-usage modelling tools

Adaptation

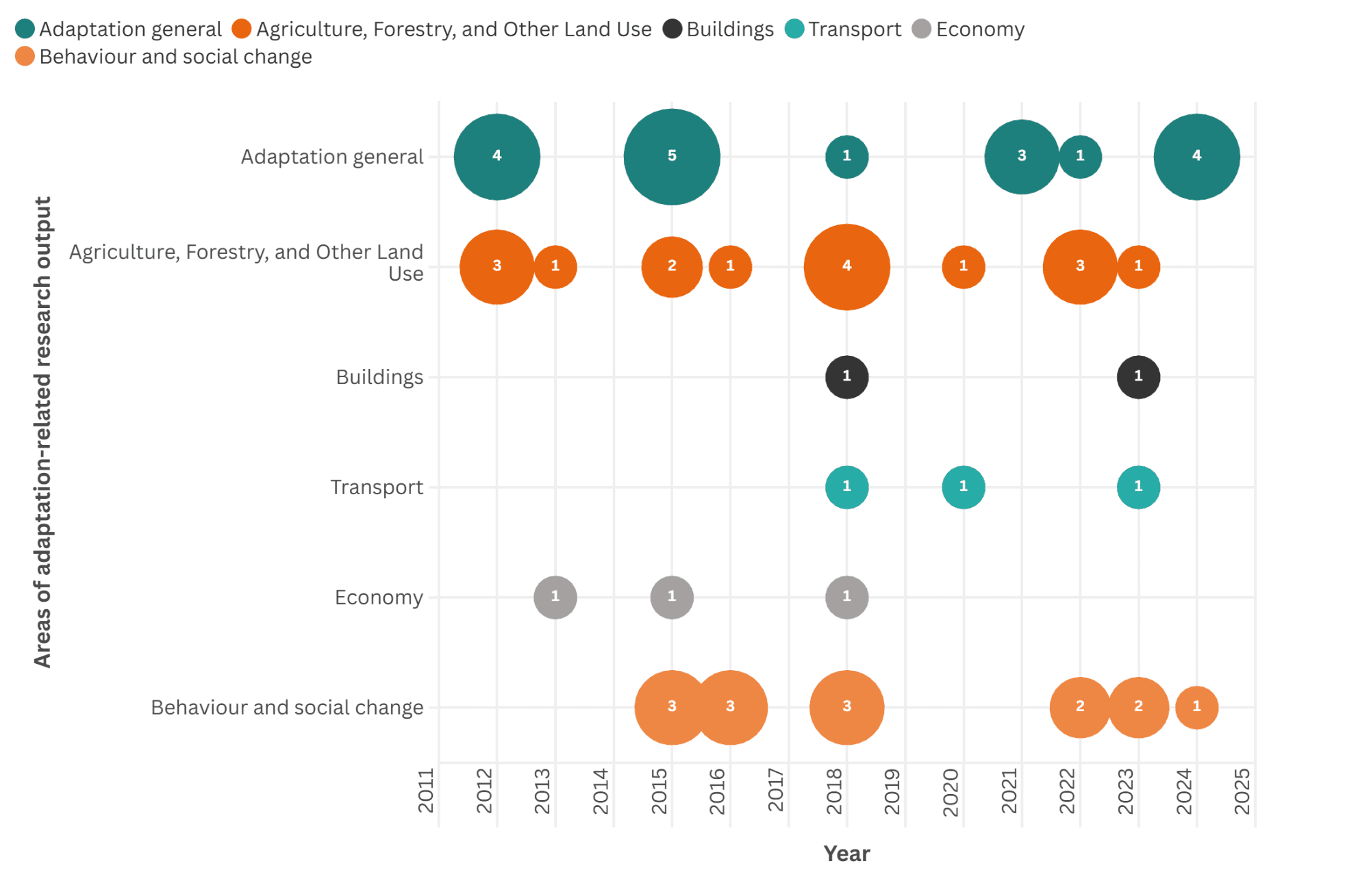

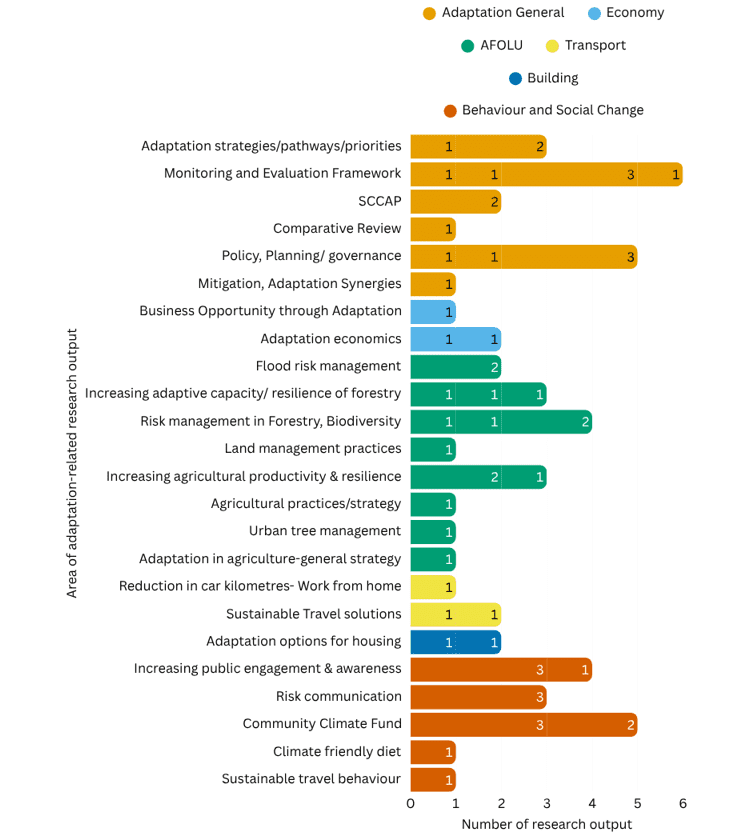

We identified a total of 56 adaptation-related research outputs, amongst which the highest evidence demand was seen in general adaptation policy topics (18 outputs) and the AFOLU sector (16 outputs). There is also a growing evidence demand on behaviour and social change (14 outputs). In comparison, there has been limited attention to adaptation economics (3 outputs), as well as sectors like transport (3 outputs) and buildings (2 outputs). The adaptation-related research outputs and themes identified are presented in detail in Figure 8 and Figure 9.

Some of the early demand for evidence about adaptation focuses on policies and potential strategies, particularly for inquiries related to the Scottish Climate Change Adaptation Programme (SCCAP), adaptation pathways, and planning. There has also been interest in monitoring and evaluating frameworks over the years, indicating a shift towards assessing the adaptation actions over time.

Compared to mitigation, adaptation-related inquiry is more diffuse. The AFOLU sector stands out with focused themes such as increasing resilience and flood management. But unlike mitigation – where energy, AFOLU and building dominate – adaptation is more fragmented with only a few sectors receiving attention. There are also clear synergies between adaptation and mitigation, with measures such as reduction in car kilometres and behaviour change contributing to both goals. While these interconnected issues have been examined, they are occasional and not systematically sought.

Impacts of climate change

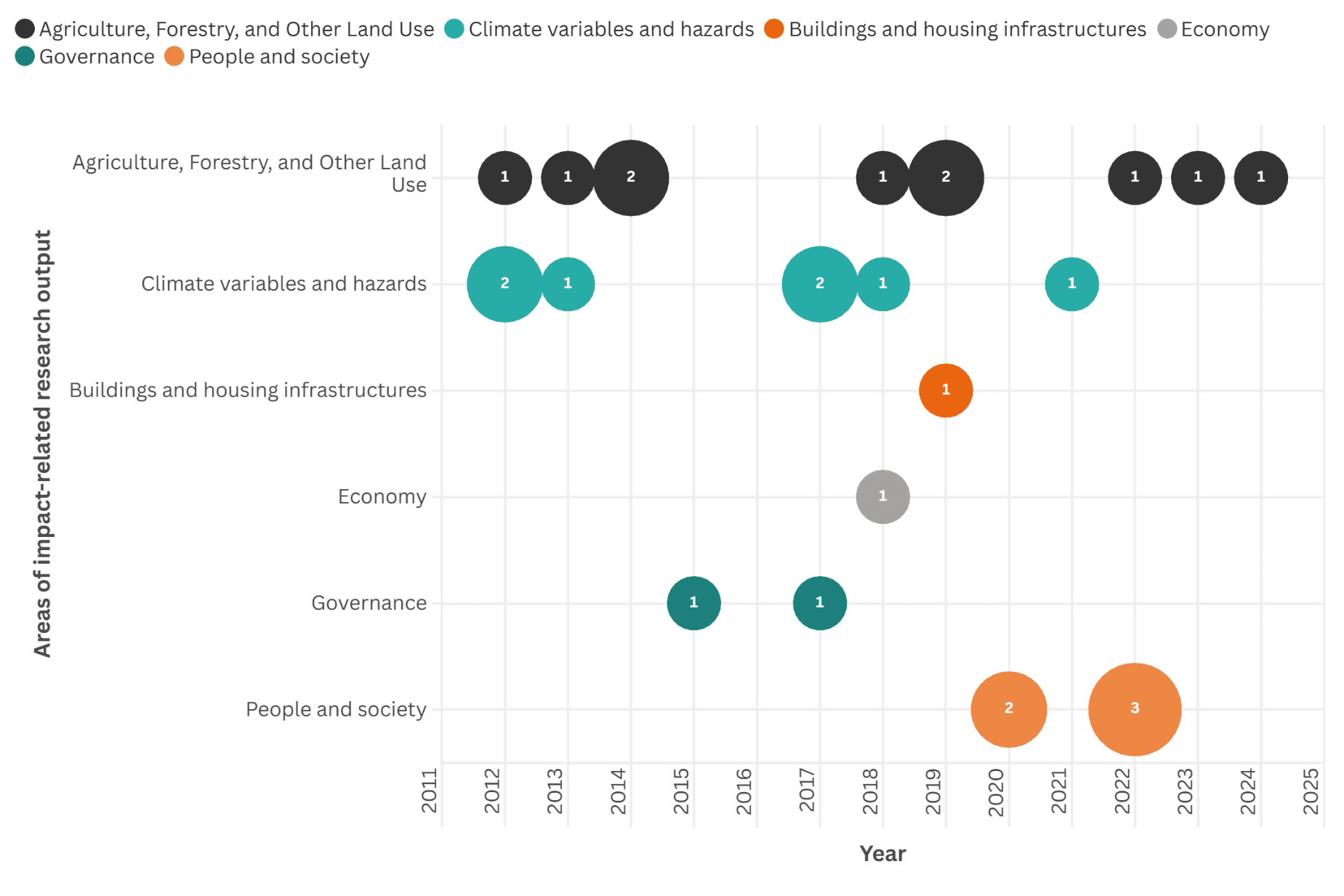

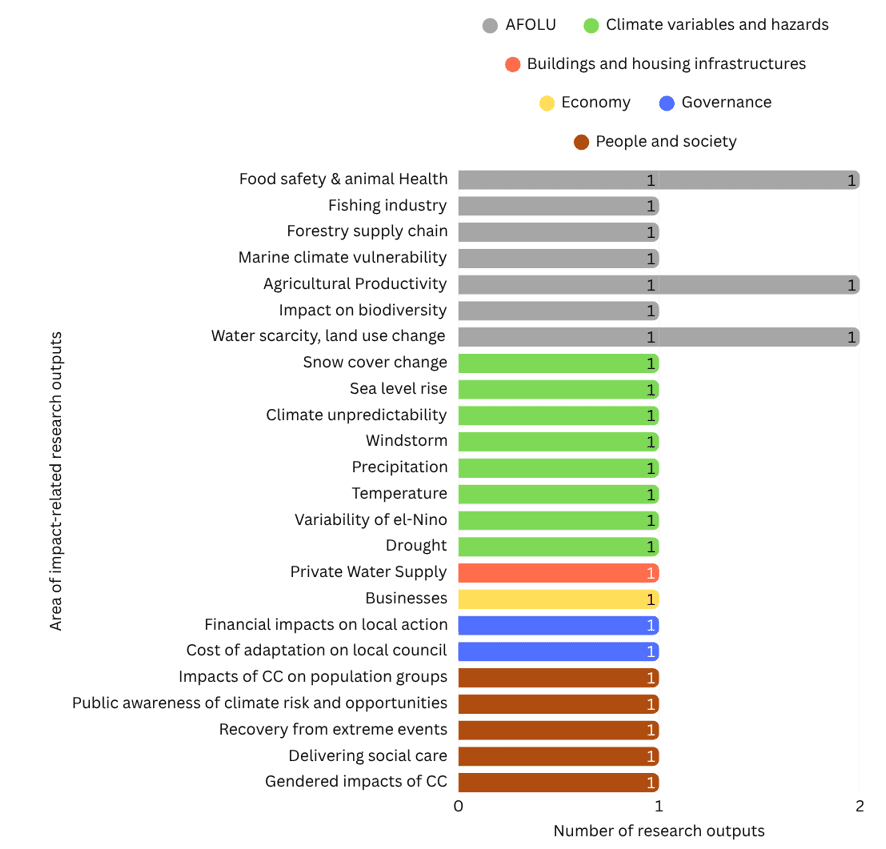

These research areas are related to the observed and projected impacts of climate change on different systems, such as population, governance or economy. We identified 26 research outputs related to climate change impacts. Areas of impact-related research outputs and themes within these areas are presented in detail in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

From the thematic analysis of outputs, the impact-oriented inquiry from the Scottish Government has been on environmental and biophysical impacts, while evidence for social and governance issues has only been sought more recently. The demand for evidence on climate impacts has had narrow temporal focus, with little follow-up over the years. Although agriculture and land use have been major areas of focus for climate mitigation, forestry-related inquires only appear for the first time in 2021.

Unlike mitigation research, which often explores connections across multiple sectors, impact-related inquiry has been more fragmented, with studies focusing on individual sectors rather than examining their interconnections. Likewise, the observed and projected impacts in Scotland have only been approached from a single-hazard perspective, rather than multiple hazards.

In the earlier phases of CXC’s publication timeline, research outputs were relatively straightforward to classify under a single sector and a single thematic area (See Appendix for details). However, as we progressed along the timeline, the complexity of projects increased, with many research outputs addressing multiple sectors and cross-cutting themes simultaneously. This shift reflects a growing recognition of the interconnected nature of climate challenges and policy responses. While integrated approaches are essential for addressing systemic issues, they also complicate knowledge brokerage efforts, as synthesising and communicating findings across multiple domains becomes more complex. The increasingly complex and cross-sectoral nature of evidence asks underscores the need for a research-policy interface that require interdisciplinary knowledge and advanced brokerage skills. This can mean that knowledge mobilisation may become harder to facilitate and translate into targeted policy actions. It also suggests researchers and knowledge brokers must interact and communicate with broader set of policy teams.

Discussion

From our review of CXC publications and the nature of evidence requested by the Scottish Government, two key discussion points emerge.

Framing of evidence needs and alignment with policy priorities

The way research needs are framed reflects the specific policy challenges or priorities that the Scottish Government aims to address. This involves examining how the evidence request corresponds to specific policy concerns, and how these evolve in response to shifting policy landscape of the government. In Scotland, research demands from policymakers to CXC have predominantly been framed around mitigation, particularly in the energy, buildings, and AFOLU sector. The demand for evidence has largely been driven by a technoscientific perspective, emphasising impact assessment, technical and financial feasibility studies, and methodologies for emission accounting. In comparison, there has been a low emphasis on social, political and governance perspectives.

Even when policy interventions could be framed through the lens of adaptation and mitigation together, they have been predominantly framed within the mitigation narrative. This was evident in areas such as food systems and transport behaviour, where the emphasis has largely been on reducing emissions rather than climate resilience for communities or businesses. This increased emphasis on mitigation-driven evidence reflects global trends prioritising mitigation over adaptation and is largely driven by legislative and international commitments that establish clear, measurable targets for emission reduction. Climate change legislation and related policies such as Scotland Climate Change Act and the legally binding net zero targets create a strong imperative for mitigation efforts, as they come with deadlines, accountability measures make them politically and administratively salient (Yule et al., 2023). Mitigation aligns more easily with economic and technological narratives that attract investment and political support (Venner et al., 2024). This mitigation-dominant framing may limit a more integrated approach that acknowledges the dual benefits of adaptation and mitigation in policy design.

However, more recently, there is a broadening demand of evidence beyond emission reduction to include risk management and long-term resilience planning. The nature of evidence demands has become significantly more intricate, requiring research that spans multiple sectors and balances competing priorities. For example, the concept of a just transition demands evidence not only on the technical feasibility of decarbonisation but also on its impact on workers, communities, businesses, and others.

Evidence demand has become more granular and place based, reflecting a shift towards insights tailored to specific sectors, agenda and context. For example, comparing the reports on the transport sector, there in an interest in not only promoting low-carbon transport but also in designing public transport systems that are accessible, equitable and effective in rural and urban areas with different needs. The complexity of climate action is now emerging; it is not just about reducing cars on the road but understanding the entire cascading system of change required. Evidence demand in Scotland has moved beyond single issue, sector specific inquiries, to complex and interrelated policy challenges that require more nuanced and interdisciplinary research approaches. Greater emphasis is also being placed upon policy experimentation and social learning.

Policymakers are increasingly engaging with complex and often competing concepts. For example, the Aitken (2014) report demonstrates how wind farm development projects, (categorised within energy and infrastructure) also raise significant social, legal, and governance considerations – including community acceptance, environmental justice, and legal compensation. The challenge for policymakers is to expand renewable energy infrastructure while also continuing to address potential local opposition and fair community benefit schemes (Aitken et al., 2014).

The need to incorporate social, economic and environmental perspectives means that research can no longer be siloed; instead, it must be interdisciplinary and require different ways of thinking and approaching research problems from those which knowledge brokers may normally be accustomed to. Therefore, as evidence demands become more complex, knowledge brokers must evolve.

Broadening demand for evidence

Although this study does not attempt to trace the uptake of evidence in policymaking, it analyses the evolving demands of policymakers, what is being asked as evidence, the type of knowledge being sought, and the responses facilitated through the knowledge brokering process. Through this lens, we observed that Scottish Government have demanded, and CXC as the knowledge broker has subsequently delivered, evidence that serves three broad objectives: instrumental evidence, conceptual evidence and anticipatory evidence.

Instrumental evidence

Instrumental evidence can be conceptualised as evidence that can directly inform and influence policy decisions and outcomes (Head, 2013). Broadly, this category of evidence has been highly specific in its demands, seeking a clearer explanation of the problem at hand, the most effective ways to address it, the available alternative options, and the optimal approaches for implementation. Instrumental evidence provided by CXC has included scientific assessments of climate impacts, identifying effective policy strategies, such as emissions calculation methods or sectoral decarbonization strategies, comparative studies of technological innovations, international best practices, evaluations of trade-offs and feasibility in policy implementation. In providing this type of evidence, CXC has largely relied on mature or emerging scientific knowledge. Not only are CXC tasked with summarising and synthesising research findings but also ensuring that they are credible and contextualised in Scotland’s unique policy landscape, including its institutional priorities.

Conceptual evidence

The Scottish Government has also sought conceptual evidence that can help policymakers better understand emerging or complex issues that may not have immediate policy applications but are crucial for long-term strategic thinking. While instrumental evidence might directly support decision-making, conceptual evidence plays a more exploratory and agenda-setting role for the distant future (Head, 2013). This includes exploring new paradigms in climate governance that go beyond technological solutions. These include a better understanding of social dimensions of climate change, such as intersectionality justice, and equity. An example of this can be seen in the report “International Climate Justice, Conflict and Gender – Scoping study” where Scottish Government sought evidence to better understand the intersection of climate justice, conflict, and gender (Duncanson et al., 2022). This research contributes to better conceptual understanding of feminist approaches and intersectionality, differential impacts (Blacklaws et al., 2024), and justice issues in Scotland’s climate change policy.

Similarly, Scottish Government has also sought evidence on integrating social equity consideration into policy interventions for land use and transport (Morton et al., 2017). Other research has also sought to answer how broader principles of fairness apply for a just transition (Abernethy et al., 2024). These concepts are central to international climate change discourse but had been relatively underrepresented or constrained within national policy frameworks, resulting in limited conceptual framing at the national level. While this conceptual evidence might not necessarily provide clear-cut answers or strategies to implement, it can shape future climate policy discourse by identifying gaps, questioning dominant paradigms, and broadening the scope of what is considered within climate policy.

Anticipatory evidence

Another important category of evidence is anticipatory evidence. Policy design is fundamentally concerned with the future and how to reach certain desired outcomes (Peters et al., 2018). Policymakers are tasked with developing solutions to problems and with each iteration of the policy process, moving closer to an ideal future by refining the design and functionality of policies (Peters and Rava, 2017, Peters et al., 2018). In this context, policymakers must create pathways to achieve goals that do not yet exist, such as a just transition. This requires not only problem-solving but also foresight to anticipate how proposed solutions can be realised. Subsequently, there is also a growing demand of anticipatory evidence from knowledge brokers, which reflects the changing nature of decision-making in climate governance. Policymakers are no longer just seeking established or emerging evidence; they are increasingly looking for insights to navigate future uncertainties. This research identified the emergence of three different kinds of anticipatory evidence that have been demanded from policymakers:

Anticipation of impacts

This type of evidence seeks to predict and assess the potential consequences of policies, technologies, or interventions before they are implemented. For example, the CXC report “Housing market impacts from heating and energy efficiency regulations in Scotland” (Benyak et al., 2024) anticipates the potential impact of the Heat in Buildings[1] Bill on the housing market. This analysis highlights the differential impact of the policy on different groups, such as first-time buyers, low-income households, and small-scale private landlords. By applying a theory of change (ToC), this study also maps out the causal pathway through which regulatory and policy options might lead to different outcomes. Theories of change often serve as an analytic tool to visualise how and why specific policy interventions are expected to generate impact (Vogel, 2012; Leach et al., 2007). In the context of evidence-informed policymaking, a ToC can also facilitate the generation of anticipatory insights by helping policymakers envision not only what should happen, but also what could possibly occur given contextual conditions (Head, 2016). There is a growing demand for this from Scottish Government within evidence-informed policymaking. This reflects a broader trend towards anticipatory and adaptive forms of governance, in which knowledge brokers are expected to understand causal pathways, assumptions, and contextual constraints.

Similarly, in response to the Scottish Government’s interest in understanding the impact of climate targets on the rural economy, the research “Climate change, the land-based labour market and rural land use in Scotland” (Atterton, 2023) was commissioned to explore the current state of the land-based labour market and the use of scenario-based modelling to project future workforce needs for achieving Scotland’s net zero targets. This work reflects a demand for relevant evidence that can anticipate the socio-economic impacts of policy interventions. The Atterton (2023) study set out to explore how climate change and policy shifts may impact rural employment, and identify potential labour shortages, skill gaps, and policy interventions needed to support a just transition through scenario-based modelling. A key finding of this study was the lack of existing data to support such modelling efforts. This report further highlights the complementary role of qualitative methods in addressing such gaps and generating context-specific insights. Together, these findings point to the need for a sustained and iterative engagement between research and policy processes. In addition, including a long-term investment in developing data or knowledge systems and collaborative research design can better align evidence production with evolving policy demands.

Anticipation of behaviour

Scottish Government has also sought evidence on how communities, businesses and other stakeholders might react to climate policies and strategies, rather than how policies should theoretically work. This includes research that has looked at behavioural shifts in favour of sustainable practices, such as sustainable travel behaviour (Colley et al., 2022, McGinley et al., 2020), adoption of electric vehicles, public transportation, or climate-friendly diets (Tregear et al., 2024). One of the key challenges in this type of evidence is that human behaviour is complex and shaped by cultural, economic contexts, making anticipation of behaviour highly uncertain and dynamic.

Anticipation of scrutiny

This form of evidence is concerned with pre-empting social acceptability or criticism, political contestations, and legitimacy challenges that climate policies or decisions might face. Not only do policymakers have to contend with the increasing complexity of climate change, but they must also design and implement solutions in policy environments that are characterised by economic and political uncertainty and technological disruption (Bali et al., 2019, Howarth and Painter, 2016).

This category of anticipation is exemplified by research on legal compensation frameworks for wind farm development (Ghaleigh, 2013). The study has examined the impacts and public opposition that wind farm projects might face, particularly around issues of legal compensation for affected communities (ClimateXChange, 2015). Similarly, research on zero-carbon heating anticipates how different income groups in Scotland might respond to the rollout of low-emission technologies. Evidence has been sought on how individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds may face varying challenges in adopting zero-carbon heating solutions, such as the upfront costs or accessibility of technology. This foresight allows policymakers to anticipate potential inequities in the transition and design policies that address these disparities, ensuring broader acceptance and fairer outcomes (Boorman et al., 2021). Similarly, anticipatory evidence on low-emission zones forecasts how people from different income groups might react to such measures, helping to identify potential resistance or disparities in the ability to comply with new regulations. By understanding these potential reactions, policymakers can plan more equitable strategies to manage and mitigate the impact of low-emission zones.

This anticipatory evidence might help policymakers foresee legal disputes and societal pushback, allowing them to design more robust policies and compensation frameworks to minimise legal risks and ensure smoother project implementation. This form of evidence use aligns with what Weiss (1979), Head (2013) refer to as political use of evidence, wherein evidence is strategically sought to pre-empt opposition and strategically align policy decisions with broader political objective. Crucially, this perspective underscores that evidence is not neutral or purely objective, rather it is shaped by normative assumptions about what issues are prioritised, what knowledge is considered legitimate, and what kind of future is desirable.

Implications for knowledge brokers

The shift in the type of evidence being demanded from policymakers highlights that the pathways to achieving climate targets have become clearer, but they coexist with increasingly complex and difficult questions. While scientific and technical solutions for decarbonisation are becoming more defined, there is growing recognition that climate action is deeply embedded within complex social systems. Issues of intersectionality, inequality, justice, gender, and vulnerability are now central to climate policy, requiring evidence that moves beyond technical feasibility to consider who benefits, who bears the costs, and whose voices are included (Upham et al., 2022). This shift also raises fundamental ethical and political questions of whether the means also justify the ends (Tangney, 2022).

As governments pursue ambitious climate goals, difficult trade-offs emerge, particularly in balancing rapid transitions with considerations of social equity and justice. In response, there is an increasing emphasis on policy experimentation and social learning, recognising that climate policies cannot be static but must evolve through iterative processes, real-world testing, and continuous feedback. This requires new forms of evidence that not only anticipate technical and economic outcomes but also assess societal acceptance, governance challenges, and long-term equity implications.

In turn, there are critical questions about the evolving role of knowledge brokering institutions in climate governance. Traditionally positioned as intermediaries between science and policy, knowledge brokers are increasingly expected to navigate contested policy spaces, engage with diverse epistemologies, and facilitate co-production of knowledge that is both scientifically robust and politically relevant (Duncan et al., 2020, Gough et al., 2021). There is an important consideration to ensure clarity on the point where evidence gathering and translation ends, and policy decision-making begins. This line is increasingly blurred as the complexity of climate change action becomes apparent. However, it remains uncertain whether existing knowledge brokering mechanisms and institutions are afforded the necessary agency, flexibility, and time to undertake such a reflexive role (Duncan et al., 2020). The institutional constraints of knowledge brokerage such as short funding cycles, rapid responsiveness to immediate policy needs, and a tendency to align with dominant policy narratives may limit their ability to fully engage with complex and critical perspectives. Addressing these issues often requires long-term, interdisciplinary research which may not be feasible within the constraints of short-term funding or the urgency of decision-making.

Conclusion

In the context of Scotland’s climate change policy, adaptation and mitigation objectives are both inextricably linked with concerns of justice, sustainable development, and long-term resilience. Our analysis shows the work of knowledge brokers has become increasingly demanding and intellectually more intensive. Beyond the technical task of translating evidence, knowledge brokers must navigate a highly politicised and evolving policy landscape, interpret multiple stakeholder priorities and help share understanding across institutional and disciplinary boundaries. This complexity calls for better institutional arrangements that recognise knowledge brokerage as a core component of policymaking. This means longer-term resourcing, dedicated time for reflection, and support for developing facilitation and deliberation skills are not just supplementary, but core competencies and enablers for knowledge brokers. These will be crucial to enable knowledge brokers to work across boundaries and respond flexibly to evolving policy needs.

Supporting knowledge brokers also means recognising that evidence use is not a linear process from research to policy. It is a negotiated process, shaped by timing, politics, relationships and context. Strengthening knowledge brokers’ position through strategic research partnerships, enabling co-production methodologies, and ensuring timely engagement with evolving policy cycles will also be crucial.

In terms of future research, this study has focused on the analysis of CXC research outputs but has not delved into the reflections of those directly involved in delivering the programme. Their experiences of managing evidence demand, navigating tensions, and working across epistemic boundaries could offer valuable insights. A follow-up study that documents the experiences of knowledge brokers themselves would add to the literature on evidence-informed policy and shed light on the evolving and often complex roles of knowledge brokers within a shifting policy landscape.

References

ABERNETHY, S., SIMPSON, E. & MULHOLLAND, C. 2024. A fair distribution of costs and benefits in Scotland’s Just Transition: findings from deliberative research. ClimateXChange Publications.

AITKEN, M., CALIRE, H. & RUDOLPH, D. 2014. Wind Farms Community Engagement Good Practice Review. ClimateXChange.

ATTERTON, J. 2023. Climate change, the land-based rural labour market and land-use in Scotland. ClimateXChange Publications.

BALI, A. S., CAPANO, G. & RAMESH, M. 2019. Anticipating and designing for policy effectiveness. Policy and Society, 38, 1-13.

BENYAK, B., HEILMANN, I., DICKS, J. & DELLACCIO, O. 2024. Housing market impacts from heating and energy efficiency regulations in Scotland. ClimateXChange Publications.

BLACKLAWS, K., KALOUSTIAN, R. & CLARK, T. 2024. Providing flexibility in heat and energy efficiency regulations – personal circumstances. ClimateXChange.

BOORMAN, A., LOWREY, C. & GOSWELL, T. 2021. Review of gas and electricity levies and their impact on low carbon heating uptake. ClimateXChange Publications.

CLIMATEXCHANGE 2015. Wind Farm Impact Study- Review of the visual, shadow flicker and noise impacts of onshore wind farms. ClimateXChange.

COLLEY, K., BROWN, C., NICHOLSON, H., HINDER, B. & CONNIFF, A. 2022. Encouraging sustainable travel behaviour in children, young people and their families. ClimateXChange.

CVITANOVIC, C., KARCHER, D. B., BREEN, J., BADULLOVICH, N., CAIRNEY, P., DALLA POZZA, R., DUGGAN, J., HOFFMANN, S., KELLY, R., MEADOW, A. M. & POSNER, S. 2025. Knowledge brokers at the interface of environmental science and policy: A review of knowledge and research needs. Environmental Science & Policy, 163.

DEWULF, A. 2013. Contrasting frames in policy debates on climate change adaptation. WIREs Climate Change, 4, 321-330.

DUNCAN, R., ROBSON-WILLIAMS, M. & EDWARDS, S. 2020. A close examination of the role and needed expertise of brokers in bridging and building science policy boundaries in environmental decision making. Palgrave Communications, 6, 1-12.

DUNCANSON, C., BASTICK, M. & FUNNEMARK, A. 2022. International climate justice, conflict and gender – Scoping study. ClimateXChange.

GHALEIGH, N. S. 2013. Legal Compensation Frameworks for Wind Farm Disturbance – Technical Report. ClimateXChange Publications.

GOUGH, D., MAIDMENT, C. & SHARPLES, J. 2021. Enabling knowledge brokerage intermediaries to be evidence-informed. Evidence & Policy, 1-15.

HEAD, B. W. 2013. Evidence‐based policymaking–speaking truth to power? Australian Journal of Public Administration, 72, 397-403.

HOWARTH, C. & PAINTER, J. 2016. Exploring the science–policy interface on climate change: The role of the IPCC in informing local decision-making in the UK. Palgrave Communications, 2.

JUHOLA, S., HUOTARI, E., KOLEHMAINEN, L., SILFVERBERG, O. & KORHONEN-KURKI, K. 2024. Knowledge brokering at the environmental science-policy interface — examining structure and activity. Environmental Science & Policy, 153.

MAAG, S., ALEXANDER, T. J., KASE, R. & HOFFMANN, S. 2018. Indicators for measuring the contributions of individual knowledge brokers. Environmental Science & Policy, 89, 1-9.

MCGINLEY, M., JAMES, N. & HOWELL, R. 2020. COVID-19, travel behaviours and business recovery in Scotland: a survey of employers to understand their attitudes. ClimateXChange Publications.

MORTON, C., MATTIOLI, G. & ANABLE, J. 2017. Low Emission Zones and Social Equity in Scotland: A spatial vulnerability assessment. ClimateXChange.

NASH, S. L. 2020. ‘Anything Westminster can do we can do better’: the Scottish climate change act and placing a sub-state nation on the international stage. Environmental Politics, 30, 1024-1044.

PETERS, B. G., CAPANO, G., HOWLETT, M., MUKHERJEE, I., CHOU, M.-H. & RAVINET, P. 2018. Designing for policy effectiveness: Defining and understanding a concept, Cambridge University Press.

PETERS, B. G. & RAVA, N. Policy design: From technocracy to complexity, and beyond. International public policy conference, 2017. 28-30.

REINECKE, S. 2015. Knowledge brokerage designs and practices in four european climate services: A role model for biodiversity policies? Environmental Science & Policy, 54, 513-521.

SCODANIBBIO, L., CUNDILL, G., MCNAMARA, L. & DU TOIT, M. 2023. Effective climate knowledge brokering in a world of urgent transitions. Development in Practice, 33, 755-761.

SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT 2024. Scottish Greenhouse Gas Statistics 2022. In: CHIEF ECONOMIST DIRECTORATE, E. A. C. C. D. (ed.). Scotland: Scottish Government.

TANGNEY, P. 2022. Examining Climate Policy-Making Through a Critical Model of Evidence Use. Frontiers in Climate, 4.

TREGEAR, A., MOXEY, A. & BRENNAN, M. 2024. Dietary guidance for healthy and climatefriendly diets: a review of international evidence. ClimateXChange Publications.

TURNHOUT, E., STUIVER, M., KLOSTERMANN, J., HARMS, B. & LEEUWIS, C. 2013. New roles of science in society: different repertoires of knowledge brokering. Science and public policy, 40, 354-365.

UPHAM, D. P., SOVACOOL, P. B. & GHOSH, D. B. 2022. Just transitions for industrial decarbonisation: A framework for innovation, participation, and justice. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 167.

VAN ENST, W., DRIESSEN, P. & RUNHAAR, H. 2017. Working at the Boundary: An Empirical Study into the Goals and Strategies of Knowledge Brokers in the Field of Environmental Governance in the Netherlands. Sustainability, 9.

VENNER, K., GARCÍA-LAMARCA, M. & OLAZABAL, M. 2024. The Multi-Scalar Inequities of Climate Adaptation Finance: A Critical Review. Current Climate Change Reports, 10, 46-59.

WEISS, C. H. 1979. The Many Meanings of Research Utilization. Public Administration Review, 39, 426-431.

WREFORD, A., PEACE, S., REED, M., BANDOLA-GILL, J., LOW, R. & CROSS, A. 2019. Evidence-informed climate policy: mobilising strategic research and pooling expertise for rapid evidence generation. Climatic Change, 156, 171-190.

YULE, E. L., DONOVAN, K. & GRAHAM, J. 2023. The challenges of implementing adaptation actions in Scotland’s public sector. Climate Services, 32.

Appendices: Plain text versions of these appendices are available via request. Please contact Saoirse Docherty at: saoirse.docherty@ed.ac.uk

How to cite this publication: Sharma, A. and Donovan, K. (2026) ‘Evolving evidence demands for Scotland’s climate change policy: Implications for knowledge brokerage, ClimateXChange. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7488/era/6857

© The University of Edinburgh, 2025

Prepared by ClimateXChange, The University of Edinburgh. All rights reserved.

While every effort is made to ensure the information in this report is accurate, no legal responsibility is accepted for any errors, omissions or misleading statements. The views expressed represent those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of the host institutions or funders.

The authors thank Grant Collinson for his support in preparation of the data visualisations for this report.

ClimateXChange

Edinburgh Climate Change Institute

High School Yards

Edinburgh EH1 1LZ

+44 (0) 131 651 4783

- Heat in Building: The Scottish Government’s legislative proposal that is aimed at decarbonising heating systems and improving energy efficiency in buildings to meet Scotland’s target of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. It sets out how Scotland plans to use its regulatory and policy levers to incentivise deployment of clean heating technologies and energy efficiencies. ↑