Assessing the impact of the Heat in Buildings Bill on leases in the non-domestic sector

Research completed: September 2024

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7488/era/5039

Executive summary

This report explores the impact of policy proposals to require non-domestic buildings to end their use of polluting heating by 2045, or before that, after being bought. These were included in the consultation on proposals for a Heat in Buildings Bill.

The point of sale trigger proposal would require property buyers to replace their polluting heating system with an alternative clean heating system, such as a heat pump, within a grace period, after purchasing a property.

These measures intend to give confidence to the market in demand for clean heating systems and support a smooth transition whereby homeowners, landlords and businesses switch heating systems at an appropriate and practical time, rather than waiting until 2045.

This project also explores the impact of proposals to introduce a requirement to upgrade heating systems in non-domestic properties at the point of property sale, or by 2045, on lease arrangements in Scotland. It explores how the proposed policies will interact with the operation of non-domestic lease arrangements in Scotland, the varying impacts of different timescales of the leases and the impact on the non-domestic property market. It also considers how existing lease arrangements could impact the ability of non-domestic buildings to comply with the policy proposals.

We conducted research on Scotland’s non-domestic property market and the proportion of different building types (e.g. offices, retail). We also explored the different types of leases and their key characteristics. This was supplemented by a review of comparable policies across Europe impacting non-domestic property leases.

These methods enabled us to assess the impact on key stakeholders, primarily landlords and tenants, with different lease arrangements. Interviews with a small sample of experts, including commercial lawyers and real estate investment companies, provided valuable insights.

Key findings

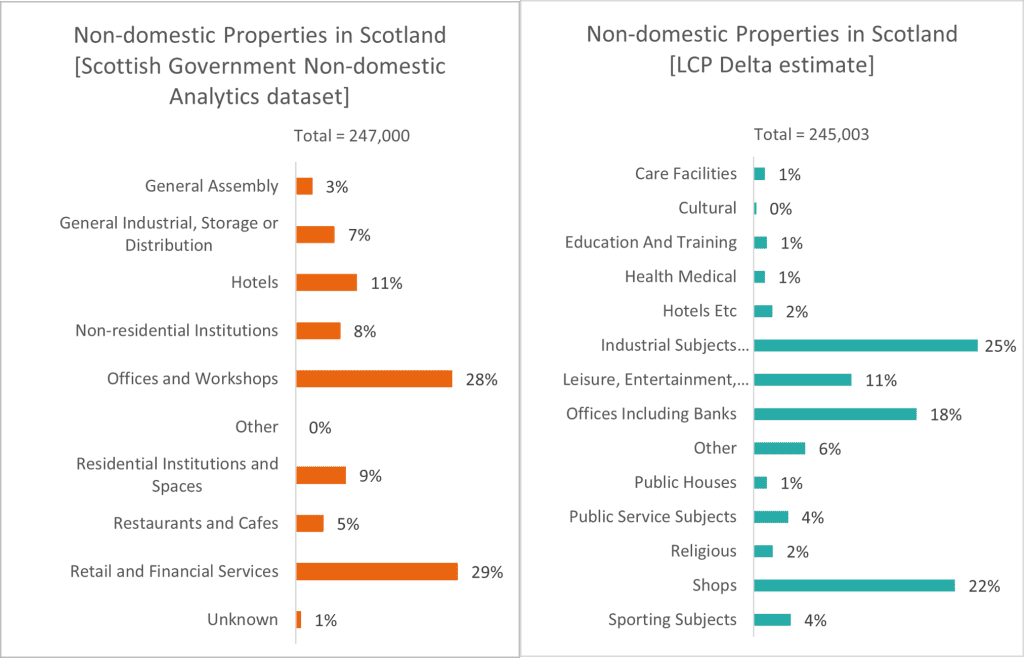

The non-domestic property market and its stakeholders in Scotland are hugely varied. As of June 2024, there are around 247,000 non-domestic properties in Scotland, with offices, factories and warehouses, and retail units making up a large proportion of these buildings.

This research highlighted the complex arrangements within the non-domestic market and the difficultly in making major changes to these buildings, such as upgrading the heating system to a heat pump or connecting to a heat network. The most significant impact would be on landlords and tenants but there is a risk of impact in the wider market, including on non-domestic property prices and abandoned buildings.

Retrofit challenges

Some non-domestic buildings have already been retrofitted to achieve higher energy efficiency. However, the proportion of these buildings is small and insufficient to meet decarbonisation targets. One interviewee commented that many businesses, particularly smaller businesses, may want to decarbonise their buildings but would not know how to do so.

Lease arrangements: landlord and tenant(s) obligations

The most common lease arrangement in Scotland is a full repairing and insurance (FRI) lease. There are some similarities in the FRI leases in different buildings but it is the clauses in each lease that determine exactly how both the building landlord and the tenant(s) are impacted if a new requirement is introduced. These clauses vary depending on factors such as the type, size and priorities of the business owning and using the building.

Through an FRI lease the aim for the landlord is to transfer any responsibility for repairing, maintaining and insuring the property onto the tenant(s). The aim of the tenant is to minimise their responsibility to pay or face disruption for repairing, maintaining and insuring the property. Where a heating system is not broken and does not fall under a repair obligation, but needs to be improved or upgraded, there would be an interest for both parties to reduce the proportion of the cost they have to pay.

Similarly, whilst less common, internal repairing (IR) leases will aim to have clear responsibility for tenant space and common building space, with both landlords and tenants wanting to minimise their responsibility.

There was a lot of uncertainty and mixed responses in our interviews with industry stakeholders, including law firms, real estate services and investment companies, on how this cost and disruption would be managed by landlords and tenants. The impact will depend both on how the legislation is drafted and the specific clauses in each contract. It will also depend on the cost and complexity of the upgrade needed to meet the requirements.

There will be complexity in all situations where the non-domestic building requires a major retrofit to comply, but the requirement becomes more challenging when it is a multi-let building (e.g. an office block with multiple different businesses occupying different parts of the building or a building used for both domestic and non-domestic purposes). In multi-let buildings, tenants usually pay a ‘service charge’ to cover costs for common parts of the building, e.g. building management services or building upkeep. In a multi-let building, it is likely that all the leases will end at different points, so there is unlikely to be an obvious trigger point when the building is empty.

Upgrade date

Most interviewees observed that having a backstop date, i.e. a requirement to upgrade all buildings by a certain date, would be easier for stakeholders to comply with than a point of sale trigger. A requirement to upgrade after the sale of the property could have a particularly detrimental impact on tenants if the cost or disruption of upgrades is passed onto them, either through a service charge or increased rent. Tenants would likely have limited or no foresight on the building being sold and would therefore not be able to build any additional costs into their business plan.

Industry engagement

The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard in England and Wales has demonstrated that there can be a lot of uncertainty around the roles and responsibilities on complying with comparable policies. The non-domestic market is complex and cannot be easily compared to the domestic market in the design of policies.

The design of the policy would benefit from close engagement with industry to minimise impacts on non-domestic building stakeholders and the market.

Glossary / Abbreviations table

|

Clean heating |

Heating system that releases little to no carbon into the atmosphere as it works to heat the home. Clean heating systems get heat from sustainable sources such as heat networks and ambient heat (heat pumps), as well as other electric systems like storage heaters. These don’t produce emissions unlike gas and oil boilers (Energy and Climate Change Directorate). |

|

Commercial lease |

As defined in the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954 (LTA 1954), a commercial or business lease is a lease where the tenant occupies the premises for the purposes of its businesses (Wilson Browne Solicitors). |

|

Communal area |

Any area that is not within the confines of the tenant’s property. For example, corridors, balconies, stairways, landings, lobbies, external gardens, bin stores, garages, and parking areas count as communal areas. The precise rules regarding communal areas in a block of flats will generally be decided by the tenants and the landlord (Jennings & Barrett, 2023). |

|

EPC(s) |

Energy Performance Certificate(s). An assessment method that defines how energy efficient a building is. EPCs rate a home from A (very efficient) to G (inefficient) (Energy Saving Trust, 2024). |

|

Grace period |

In the context of the consultation for proposals for a Heat in Buildings Bill, a grace period refers to a specified duration given to building owners/tenants to have the upgrade work carried out, including the time to have the buildings assessed and/or to receive quotes from installers as necessary. |

|

HiB |

Heat in Buildings Bill |

|

Lease |

A contract between the landlord and the tenant that gives the tenant the exclusive right to occupy and use the landlord’s property for a period of time. Like any contract, the lease terms are based on the needs and situations of both the landlord and tenant when the lease is created (Wilson Browne Solicitors). |

|

Multi-let |

A rental agreement between a lessor and several lessees in a larger, multi-unit property. However, it is also common for lessors to rent out each unit in a multi-let property individually to a single tenant (Binary Stream, 2022). |

|

Polluting Heating |

A heating system that produces harmful gases into the atmosphere at the point of use within the building (direct greenhouse gas emissions), such as gas, oil, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) boilers or burners, and bioenergy systems. |

|

Retrofit |

Retrofit is the introduction of new materials, products and technologies into an existing building to reduce the energy needed to occupy that building. Retrofit is not the same as renovation or refurbishment, which often make good, repair or aesthetically enhance a building without aiming to reduce its energy use (Technology Strategy Board, 2014). |

|

Service charge |

Means by which a landlord can recover from tenants the cost of maintaining and repairing a building and providing certain services. Typical costs can include: repairs extending to major structural repairs and general maintenance services, including cleaning, waste collection, lighting, heating, air-conditioning, and security (RICS, 2024) |

|

Single let |

A rental agreement between a lessor and the sole lessee of a property (Binary Stream, 2022). |

|

Trigger point |

Key moment in the life of a building (e.g. rental, sale, change of use, extension, repair or maintenance work) when carrying out energy renovations would be less disruptive and more economically advantageous than in other moments (BPIE, 2015). |

Introduction

Policy context

Scotland has legally binding targets to achieve ‘net zero’ greenhouse gas emissions by 2045. Currently non-domestic buildings accounting for around 6% of Scotland’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

Following the publication of the Heat in Buildings Strategy in 2021, the Scottish Government published the ‘Delivering net zero for Scotland’s buildings – Heat in Buildings Bill: consultation’ in November 2023. Within this consultation there was a proposal to introduce a new law which will prohibit the use of polluting heating from 2045 and require those purchasing a property to comply with the prohibition on polluting heating within a specified amount of time following completion of the sale.

Under this proposed law, a ban will apply to the use of all polluting heating systems from 2045, in line with the 2021 Heat in Buildings Strategy. The consultation also asked for views on a property purchase trigger. Under this proposed law, the purchaser of a property will be given time (a grace period) to have the work carried out, including time to have their building assessed and / or to receive quotes from installers as necessary. The consultation sought views on the length of time the grace period should last for both domestic and non-domestic properties, proposing between 2-5 years. This is intended to balance the need to treat the new building owner fairly with the need to make progress in reducing emissions. There was also a question in the consultation on whether to apply the requirements to all commercial long-term leases registered with the Registers of Scotland in addition to sales of non-domestic properties.

Current progress towards decarbonising non-domestic buildings

Most interviewees observed that the non-domestic building market is already transitioning to low carbon solutions or that there is an interest from businesses to decarbonise their buildings. There is a growing trend for companies to focus more on their Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) commitments, and consequently seek out energy efficient workspace (UK Green Building Council, 2024b). In addition, recent energy price spikes have caused businesses to be more aware of their energy consumption and identify ways to reduce it (Federation of Small Businesses, 2023).

Some interviewees observed that there have been increasing examples of commercial retrofits taking place in Scotland to improve energy efficiency. For example, an office space at 4-5 Lochside Avenue, Edinburgh Park provides a good example of retrofitting an existing commercial building to an EPC B+. In this case, Knight Property Group took the decision not to demolish the original building but to comprehensively remodel, develop and refurbish the building instead. They replaced the gas-fired boilers with an efficient electric heating system and aligned to Net Zero targets and the anticipated Scottish Government ‘New Build Heat Standard’. The upgrades allowed the building to then be marketed as a ‘high quality office space in an all-electric facility aligned to net zero policies’ (UK Green Building Council, 2022). The strong environmental credentials were reported as being a key attraction for the new tenants who took on a 10-year lease (The Edinburgh Reporter, 2023).

It is recognised by industry representatives that commercial buildings are not being retrofitted at the scale needed to achieve decarbonisation targets (UK Green Building Council, 2024a). Larger organisations, such as investment companies, are likely to have already started decarbonising their buildings either in anticipation of future requirements or due to a demand from tenants for greener buildings. However, the lack of clarity around targets and support is causing delay or hesitancy among smaller, less strategic investors or owners (UK Green Building Council, 2024b). One interviewee, a large real estate investment company, stated they ‘have already started decarbonising our building stock and have noticed this happening much more in the market over the last 8-10 years but smaller landlords are less likely to be doing this’. The HiB policy proposals aim to give confidence to the market in the demand for clean heating systems, including organisations who may not currently have plans to decarbonise their buildings.

In England and Wales, data published by the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) has shown that there has been some decrease in energy consumption on non-domestic buildings, but the pace of change is slow (DESNZ, 2024). Between 2012 and 2022 there has been largely stable gas consumption, except for a drop in 2020 due to Covid disruption and slightly reduced electricity consumption. In Scotland, electricity consumption in the non-domestic sector has remained relatively stable, with only a 0.1% increase from 2020 to 2021, while gas consumption decreased by 2.5% during the same period (Energy and Climate Change Directorate, 2022). Furthermore, in England and Wales, the top energy consuming sectors have been identified as offices, retail, industrial, health and hospitals, which jointly account for 71% of non-domestic energy consumption ( (UK Green Building Council, 2022).

Research aims and scope

Project scope and aim

ClimateXChange commissioned LCP Delta to undertake research into the impact of proposed clean heat regulations on non-domestic property leases, focusing on:

- How the proposed policies interact with operation of non-domestic lease agreement types in Scotland.

- The varying impacts of different timescales on leases, i.e. requirements to upgrade before the backstop or sooner due to a property purchase trigger.

- Comparable policy changes that have previously been introduced in the non-domestic property market, and lessons from the implementation and review of these policies.

- How duties and burdens are likely to fall on different parties in the sector.

Approach

The project was split into five key stages:

- Desk-based research on Scotland’s non-domestic property market to provide a base understanding of Scotland’s non-domestic property market. This also included research on the key lease types used in Scotland.

- Investigation into similar property mechanisms across Europe. We used LCP Delta’s existing heat policy database and additional desk-based research to identify comparable policies impacting non-domestic property leases.

- Development of an analytical framework to provide a systematic and robust qualitative assessment of the impact of the HiB Bill proposals on non-domestic lease agreements and market actors.

- Interviews with industry experts to input on the analysis of the impact of HiB Bill proposals on different lease types.

- Interviews with industry experts to explore the impact on wider market dynamics, for example property prices and turnover rates.

This report sets out the findings from this research which was conducted between July-September 2024.

Interview approach

We caried out eight interviews for this project with a range of experts on Scotland’s non-domestic property market. The aim of these interviews was:

- To validate our analysis on different lease types and the impact on key stakeholders, and

- To capture expert views on the impact on wider market dynamics, for example property prices.

Stakeholders were identified using desk-based research and using Scottish Government and LCP Delta networks and market knowledge. Stakeholders were selected based on their expertise on the Scottish non-domestic property market. We focused on both law firms and real estate services and investment companies due to their expertise on lease arrangements and the process of upgrading non-domestic buildings. The companies interviewed were:

- Two law firms

- Three real estate services and investment companies (one of these organisations we interviewed twice to get their views in the early stages and to test our analysis with them)

- Registers of Scotland

- Federation of Small Businesses

We started each interview with an overview of the policy and the aim of the project and provided key definitions (e.g. polluting heating system) to ensure clarity on what was being discussed. A discussion guide was developed ahead of the interviews, with questions including:

- Could you provide any insights into the structure of Scotland’s non-domestic property market? E.g. size of the market, shape of the market (e.g. type of non-domestic buildings)

- How do you see the impacts changing if the grace period was 2 years vs 5 years?

The interviews were interviewee led, with some flexibility to allow interviewees to discuss what they considered to be the key points. Two project team members were present in each interview, with one leading the discussion and one taking minutes.

Research limitations

As this project was a broad, desk-based study the project team focused on ensuring relevant policies from other countries were identified that provided a range of learnings. It was not possible within the timeframe to investigate each of these policies extensively. A more detailed analysis or engagement with policymakers could be undertaken to understand the lessons learned from each policy in more details.

The small sample of eight interviews provided valuable insights from experts that would be directly impacted by, or are working with key stakeholders that would be impacted by, the HiB Bill policy proposals. This allowed an analysis of the likely impacts to be made for a set of broad scenarios. Further analysis and engagement with stakeholders would be required to understand more specific impacts, a more detailed understanding of the impact on different stakeholders, lease arrangements and building types. As suggested by two interviewees, this could be in the format of a series of trials where a few geographical areas are chosen to understand the lease arrangements in place and the impact if the policies were introduced.

Overview of Scotland’s non-domestic property market and lease arrangements

Scotland’s non-domestic buildings are extremely varied, ranging from new office blocks in Edinburgh, to small guest houses on the Isle of Mull and large retail units in Perth. Any policy introducing new requirements on these buildings will therefore need to consider the size and diverse nature of the building stock and its stakeholders.

The Scottish Government’s Non-Domestic Analytics dataset indicates that there are about 247,000 non-domestic properties in Scotland as of July 2024. This figure was derived based on combination of input from OS AddressBase, Scottish Assessors, and Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) records. Where data for specific properties was unavailable, the Energy Savings Trust modelled the information. The model uses Energy Savings Trust’s in-house tool and accounts for a significant proportion of the non-domestic property data (Scottish Government, 2024).

We then sought to determine the number of non-domestic leases using publicly available data, including by engaging with stakeholders such as the Registers of Scotland (ROS). From our engagement with ROS, it was noted that no publicly available dataset provides detailed and accurate information on the number and types of non-domestic leases. However, ROS experts highlighted that real-time statistics on non-domestic properties are tracked by Scottish Assessors and can be accessed publicly via the Scottish Assessors Valuation Roll. For context, the Non-Domestic Analytics dataset also uses data from Scottish Assessors data as an input. Scottish Assessors is an association of independent public officials who compile valuation rolls that list details of buildings and other property in their respective areas (Scotland’s People, n.d.). The valuation roll is a public document that includes entries for all non-domestic properties in each of Scotland’s 32 local councils, except those specifically excluded by law (Scottish Assessors, n.d.). New properties are added to the valuation roll when they are built or occupied and are removed when, for example, they are demolished. The valuation roll serves as the basis for the administration of valuation, council tax, and electoral registration services.

Recent statistics retrieved from the Scottish Assessors Valuation Roll on 9 August2024 report a total of 262,024 non-domestic properties in Scotland (Scottish Assessors, 2024). This figure still includes non-heating properties, such as quarries and monuments. When excluding these non-heating properties, we estimate that around 245,000 non-domestic properties in Scotland require heating per this database. See Appendix A for details on how this value was derived.

Figure 1 presents a comparison of the total number of non-domestic properties in Scotland, categorised by property type, based on the Scottish Government’s Non-Domestic Analytics dataset, with LCP Delta’s estimate derived from the Scottish Assessors Valuation Roll. Both datasets show a comparable total number of non-domestic properties, with only a 0.8% difference. It’s important to note that the two datasets use different property type classifications, and no effort was made to harmonise these classifications. Therefore, both datasets could be used as a valid basis for future work. If a more detailed breakdown by property type is required—for example, to ensure that impact assessments for the Heat in Buildings Bill cover as many property types as possible—the standalone Scottish Assessors dataset can be utilised.

Commercial leases in Scotland

A commercial lease is a contract between a landlord and a business tenant. The lease grants the tenant the right to use the property for a commercial purpose over a set period for an agreed rent. The lease will also outline the rights and responsibilities of the landlord and the tenant during this period.

The clauses in commercial leases in Scotland are not standardised. As such, terms and obligations vary significantly across contracts. In England and Wales Landlord and Tenant legislation governs commercial property leases, which aims to protect the rights and interests of tenants (Shepherd Wedderburn, 2019). Alongside this, there is a ‘Code for Leasing Business Premises’ which is a partially voluntary code, developed by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) as a professional standard, setting out what are considered to be fair terms that should be offered to tenants. This does not apply in Scotland and there is more limited legislative protection for commercial tenants in Scotland.

For years, commercial property solicitors in Scotland have sought a standard form of commercial lease that would bring a degree of clarity and unification to the complex area of commercial leasing. The Property Standardisation Group (PSG) was formed in 2001 to create more standardisation for documents and procedures in Scottish commercial property transactions. Whilst the PSG provides standard templates for contracts, one interviewee (a law firm representative) acknowledged that many contracts still will not follow this approach since there is no obligation to do so. If there are already leases in place it is likely parties would continue to use that format and even if they start with the PSG format it is likely there will be negotiations to change certain clauses.

Types of leases

We carried out desk-based research to identify the key lease types used in non-domestic properties. Landlord and tenant law, and lease arrangements, has been an under-researched area of Scots law (Norbash, 2022). Most interviewees commented on the complicated and varied nature of commercial leases with one stating ‘every lease is different and there is no standard’. Through our research we have identified two key categories of lease for commercial properties in Scotland:

- Full repairing and insurance lease

- Internal repairing lease

Within each of these lease types there will be a lot of variety in the clauses used within them. However, we’ve provided an overview of the key criteria of each below.

Full repairing and insurance leases (FRI) were reported to be the most common form of commercial property lease in Scotland by interviewees and industry reporting (Murray Beith Murray LLP, 2021). An FRI is used in scenarios where the tenant utilises the full building and is also common in multi-let buildings. Through this lease landlords aim to transfer their landlord’s common law responsibility of repairing, maintaining and insuring the property on to the tenant (Edwards, 2007). The tenant, on the other hand, will want to try and minimise their repair obligations under the lease as much as possible.

Ahead of entering the contract there will be negotiations on the clauses in the contract around the rights and obligation of the tenant. Tenants will usually aim to avoid having clauses in the contract which allow the cost of, for example, a new heating system to be transferred onto them or to allow a major upgrade which causes significant disruption to their business. If the existing heating system is not broken and needs upgrading to comply with new requirements it is likely this would not fall under a ‘repair’ obligation on the tenant. Tenants will usually seek to have a clause to remove the ability of the landlord to put improvement costs into the service charge. (Pitt & Noor, 2009) observed that ‘a well-drafted service charge provision in the lease is a crucial element that needs special attention by the tenant to avoid future disputes with the landlord. Where this is not in place, or the terms in each contract with the tenants vary, it will become very complicated. There are different approaches landlords can take to apportioning the service charge among tenants. These include based on floor area occupied by the tenant or a fixed percentage. One interviewee stated that ‘service charge regimes will be different for every tenant. Tenants may have something they’re willing to pay for as a tenant and fought hard for that’.

In multi-let buildings, such as office blocks, the dynamics of FRI leases can vary between tenants. FRI arrangements in multi-let buildings can be referred to as Effective Full Repairing and Insuring Lease (Effective FRI). Usually, the landlord is responsible for repairing the structure of the building and common areas and they will pass on costs back to the tenant through the service charge (Noor and Pitt, 2009). The tenant will be responsible for arranging maintenance and repairs to the internal elements of their part of the building. In these multi-let buildings it is important to both the landlord and the tenant that the description of the premise in the lease is clear, with clear obligations around different elements such as the floors and walls. In the event that repair or improvements are required to the structural elements of the building, such as the roof or the lift in a communal area, the landlords may be able to recover the costs though the service charge, depending on the clauses in the contract.

Internal repairing leases (IR) are less common within commercial property and most new leases will be FRI. These IR leases will mean that the tenant is only responsible for the upkeep and repairs to the internal elements of their part of the building (Vickery Holman, 2024). IR leases can be used in multi-let buildings (e.g. an office block with multiple different companies / tenants in separate offices). With these leases the tenant will have a narrower liability for maintenance, decorations, repairs and insurance limited to the internal parts of the property they occupy.

For all these lease types, the clauses in the contract are key to understanding obligations around repair and improvements, and there will be negotiations on the rights to enter, make changes and cover costs through the service charge. Many tenants aim to remove the landlord’s ability to make changes to their premise that cause disruption to their business or be charged for these changes through the service charge. Tenants will usually employ service charge consultants to negotiate these terms for them.

In a multi-let building it is likely that there will be differing contract arrangements for the different tenants in the building. For example, it is likely that larger organisations will have stronger bargaining power to negotiate the clauses, and therefore more likely to be able to remove clauses to pass the obligation or cost of heating upgrades onto them. A smaller organisation may have less bargaining power to do so.

Different businesses will also have different priorities in the negotiations so while some may accept certain clauses in a contract others may put a lot of work in to negotiating the clause out of the contract. For example, a tenant taking on a longer lease (e.g. 15-20 years) is more likely to accept some obligation or cost for new heating systems as they will experience more benefit from it. A tenant taking on a shorter contract (e.g. 5 years) is much less likely to accept paying for a new system.

The aim of any non-domestic lease contract is to have every element of the building covered by either a tenant or landlord responsibility. However, in practice, when an obligation comes onto the building there may be uncertainty around whose responsibility it is due to vagueness in the contract. Where there is vagueness in the contract leading to uncertainty over whether it is the landlord or tenants’ responsibility to take on the burden / cost of changes to the property, it can be a challenging situation and legal disputes can follow. Interviewees cited examples in which the responsibility over the air conditioning and its different components (e.g. plant, vents etc.) has been unclear from the contract, resulting in challenging negotiations between landlords and tenants.

Lease duration

There has been a trend of contracts getting shorter and this has been accelerated by companies exercising more caution after Covid. Most interviewees commented on this point with one law firm representative stating “leases today are generally quite short, I haven’t seen any more than ten years for a while”. It used to be fairly common to have 25-year leases but today most leases are much shorter (Garrity & Richardson, 2019). Some interviewees stated that they haven’t seen anything longer than a 10-year lease in many years and it is likely that a 10-year contract would have a break clause of 5 years. Lease length may also depend on the type of building, with offices tending to have shorter leases and industrial or warehousing leases being longer, to reflect that tenants are less likely to move on quickly (Birketts, 2021). One interviewee commented that longer leases do exist, citing one recent example they had seen of a 35-year lease.

This is an important factor when considering the obligation of new heating systems as tenants are less likely to accept disruption or cost for a new heating system when they only have a contract of a few years. Where a tenant has taken on a lease of 20 years, they may be more accepting to take on the cost or disruption of the system. This is due to the fact that 20 years is a similar time period to many heating system’s lifetime and the tenant will be able to benefit fully from the new system. However, it is a likely that a tenant with a 5-year lease would perceive any significant cost or disruption associated with a new heating system as disproportionate to the benefit they will receive.

In a multi-let building it is likely that there will be contracts with varying lengths of time left on them. This is illustrated in Table 1 below, which presents an example of the lease durations in an office block with six tenants. For example, some tenants may only have one year left on their contract, but the tenant next door may have just moved in and have eight years left on theirs. These tenants will have different views towards upgrading their heating system. For example, those with only a year left on their contract, and therefore only a year to benefit from a new heating system, are likely to be more resistant to paying for an upgrade or having disruption to their business caused by the upgrade. In many cases a communal heating system will be more efficient than separate systems in each part of the building.

Table 1: Hypothetical Illustration of multi-let office building with varying lease lengths in place

|

Lease period | ||||||||||||||

|

Office unit |

Year 1 |

Y2 |

Y3 |

Y4 |

Y5 |

Y6 |

Y7 |

Y8 |

Y9 |

Y10 |

Y11 |

Y12 |

Y13 |

Y14 |

|

Office 1 |

Tenant 1 |

Tenant 2 | ||||||||||||

|

Office 2 |

Unoccupied |

Tenant 1 | ||||||||||||

|

Office 3 |

Tenant 1 |

Break clause |

Tenant 2 | |||||||||||

|

Office 4 |

Tenant 1 | |||||||||||||

|

Office 5 |

Tenant 1 |

Tenant 2 |

Tenant 3 | |||||||||||

|

Office 6 |

Unoccupied | |||||||||||||

Development of green leases in Scotland

There has been work towards developing ‘green lease’ clauses by the Better Buildings Partnership (BBP).[1] BBP argue that green leases are an important tool to ‘help to transform the environmental and social impact of a building’. They aim to support landlords and tenants by having a clear legal framework that establishes the roles and responsibilities for the delivery of environmental and social outcomes (Better Buildings Partnership, 2024). The BBP provide guidance and suggested wording for clauses in commercial leases that will support the decarbonisation of buildings. The BPP is a UK wide initiative and provide specific clauses for buildings in Scotland. There is no requirement to follow this guidance so any parties using these green leases will be doing so voluntarily. Green leases are becoming more utilised, but they are not widely used in the market. It is expected that as requirements for energy efficiency become more stringent and imminent more leases will seek to include green clauses (The Law Society, 2023).

Key learnings from similar policy mechanisms across Europe

We have identified several relevant policy mechanisms across Europe that have been previously implemented to promote clean heat in leased non-domestic buildings. The following section gives an overview of relevant policies and explore lessons learned.

Policy overview

Across Europe the regulatory landscape for clean heating in non-domestic buildings is relatively nascent. Most countries are yet to make significant progress with decarbonising their existing building stock. In the European Union, 85% of buildings were built before 2000 and 75% of those have poor energy performance (European Commission, 2024). There is also much less research and comprehensive data gathered for non-domestic buildings in Europe compared to domestic buildings, partially due to the varying nature of the non-domestic building stock (Kiviste & Musakka, 2023).

The revised EU Energy Performance of Buildings Directive in 2024 introduced a requirement for the gradual introduction of minimum energy performance standards for non-residential buildings based on national thresholds to trigger the renovation of buildings with the lowest energy performance. There have also been policies set in many European countries on the standards of new builds to reduce their CO2 emissions and environmental impact (World Green Building Council, 2022).[2] There have also been regulations introduced in many countries requiring decarbonisation of domestic buildings.

Table 2 shows the key information on relevant policy mechanisms that we have identified across European countries. Details for each policy mechanism is available in Appendix B.

|

Policy title |

Applicable to |

Description |

|

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard (MEES) |

England and Wales |

Privately rented properties must have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) and meet a minimum EPC rating of E, with plans to raise this to B by 2030, and includes various exemptions and penalties for non-compliance. |

|

Section 63 of the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009 – The Assessment of Energy Performance of Non-domestic Buildings (Scotland) Regulations 2016 |

Scotland |

Owners of non-domestic buildings over 1,000 m² must provide a valid EPC when selling or leasing to a new tenant. Buildings that meet 2002 energy standards or already improved through a Green Deal are exempt, since they are considered to be reasonably efficient. |

|

Tertiary Decree (Decret Tertiaire) |

France |

All tertiary buildings[3] over 1,000 m² must gradually reduce their energy consumption, with annual reporting to ADEME and fines for non-compliance. |

|

Renovation obligation |

Belgium (Flanders and Brussels) |

In Flanders, non-domestic properties must replace central heating systems older than 15 years with new, compliant heat generators as part of the Flemish Energy and Climate Plan. Brussels announced a similar regulation to be enacted in the region starting from 2024. |

|

Energy label C offices |

Netherlands |

Commercial offices must have a minimum EPC rating of C or higher by 1 January 2023. |

|

Building Energy Act 2024 |

Germany |

Requires newbuilds in specific areas to use at least 65% renewable heating/cooling starting from 1 January 2024 (with varying deadlines for each municipality), effectively banning fossil fuels-based heating systems. |

|

Heat Network Zoning |

Scotland and England |

Heat network zoning is a process to designate areas where heat networks are expected to be particularly suitable and offer the lowest-cost solution for decarbonising heat. |

|

Energy Climate Law (Heat networks) |

France |

The classification allows a local authority to impose the connection to a heating network within a priority development area. Within a specific area surrounding the network, referred to as the priority development area, it is mandatory to connect to the heating network for:

|

Table 2 Policy mechanisms for heating in non-domestic properties in other countries

Successes and lessons learned

Promoting building energy efficiency and clean heating in the commercial real estate market

The French Tertiary Decree has raised awareness about energy efficiency improvements and clean heating within the real estate sector by establishing maximum annual final energy consumption targets that all stakeholders—whether owners of owner-occupied spaces, lessors, or tenants—must report each year. While financial sanctions for non-compliance are relatively modest (€1,500 for individuals and €7,500 for legal entities per building concerned), the decree includes a ‘name and shame’ mechanism (BMH Avocats, 2021).

As a result, the Tertiary Decree has led to significant changes in commercial real estate practices. According to CBRE Rive Gauche, a commercial real estate agency, the regulation has become central to real estate discussions, particularly concerning shared responsibilities like cost coverage and action management. Buyers and tenants are increasingly favouring tertiary buildings that meet the standards set by the decree and do not require major energy efficiency upgrades. The decree has also increased pressure on older, unrenovated buildings, making them less attractive to tenants and buyers, highlighting the critical need for energy renovations (CBRE Rive Gauche, 2024). France is particularly pushing for energy renovations and retrofitting where possible, rather than developing new buildings, as local authorities (municipalities) consider demolition a last resort (Real Asset Impact, 2024). There are financial incentives to help with energy renovation costs and clean heating, such as the Coup de Pouce Chauffage program (Ministry of Ecological Transition and Territorial Cohesion, 2024), which have driven the adoption of heat pumps in the tertiary sector (Ministy of Energy Transition, 2023a). The French Heat Pump Association highlighted a significant increase in the market share of heat pumps for retrofitting in the tertiary sector, rising from 7% in 2020 to 26% projected by 2026 (AFPAC, 2023).

Historically, the tertiary sector, which accounts for around 17% of France’s final energy consumption (ADEME), has shown an increasing trend in energy consumption (Hellio). The tertiary sector is also the second largest emitter of greenhouse gas in France (TotalEnergies, 2024), with a significant proportion of their final energy consumption still coming from petroleum products and natural gas (Ministry of Energy Transition, 2023b). Businesses typically did not prioritise energy savings or more specifically, clean heating, in the absence of regulatory obligations. However, since the introduction of the Tertiary Decree, it has been reported that many entities in the tertiary sector have made significant efforts to reduce their energy consumption while continuing to grow their business activities (Big media, 2024). Currently, the energy consumption of more than half of the French tertiary sector, covering nearly 600 million square meters, is being monitored by ADEME (ADEME).

A study also highlighted that the Dutch Energy Efficiency Policy for Offices, which mandates a minimum energy label of ‘C’[4], has significantly driven energy renovations in office buildings compared to other commercial property types. Between 2018 and 2022, after the policy was announced, approximately 75% of office renovations improved the building’s efficiency rating to energy label ‘A’ or better. Notably, about 32% of these renovations involved office buildings that previously had an energy label of ‘D’ or worse. In contrast, only 17.5% of renovations in other commercial properties with an initial energy label of ‘D’ or worse achieved an upgrade to energy label ‘A’ or higher (Maastricht Center for Real Estate, 2023). Additionally, another CBRE report highlighted that office buildings with energy labels of ‘A’ or higher are now the most popular for commercial lettings, indicating a growing demand for highly efficient office spaces (CBRE, 2022). The report also noted that traditional financiers are becoming increasingly reluctant to invest in non-sustainable real estate, and when they do, they tend to offer loans at higher interest rates.

Lack of clarity

Some industry sources suggest that there has been confusion around the responsibilities incurred by and application of the non-domestic private rented Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard (MEES) in England and Wales. Landlords are the legal party obligated to deliver MEES but there are impacts and costs that could be passed on to tenants. MEES is likely to impact decisions around service charges, alterations and lease renewal negotiations for many landlords.

Opinions on MEES include that:

- ‘Government guidance is difficult to navigate in respect of lease renewals given the differing advice under the EPC and MEES regulations’ (Gordons LLP, 2023). The EPC Regulations 2012 require landlords to provide a valid EPC when selling a building, but not for lease extensions or renewals. However, MEES regulations mandate that if no valid EPC exists, a new one must be provided when leasing to an existing tenant. Failure to do so could technically prohibit lease extensions or renewals, highlighting inconsistencies between the two regulations (Gordons LLP, 2023).

- The current position in England and Wales will be creating a lot of uncertainty for landlords and tenants and many will be asking themselves:

- If their lease allows the landlord to enter the property to carry out improvement?

- And if so, what protection is given to the tenant to prevent significant disruption to their business?

- And whether the landlord can pass these costs to the tenant? (Mullis & Peake LLP, 2023)

There has also been a lack of enforcement of MEES with an industry investigation finding that local authorities, who are responsible for enforcing MEES, taking little to no action to enforce it (CMS, 2024). This is largely due to local authorities taking a ‘whistleblowing’ or reactive approach to enforcement due to lack of funding for enforcement.

Policy loopholes

The implementation of the MEES in England and Wales has faced challenges due to its complex policy design. In 2011, the UK Government announced that starting April 1, 2018, properties must meet a minimum performance standard at the point a letting when a lease agreement is made. As a result, until 2023, only leased properties are required to meet this standard, leaving owner-occupied properties excluded from the policy scope. Furthermore, having lease renewals as the trigger point for compliance means that, due to the continuity of occupancy, there may not be an appropriate window for the necessary upgrade work (McAllister & Nase, 2019).

The Flanders renovation obligation in Belgium also has a few loopholes, where some transactions are not subject to the legislation. As an example, a triple net lease instead of a long-term lease does not trigger the obligations. For context, a triple net lease is a commercial lease agreement where tenants pay all expenses in addition to the cost of rent and utilities, which typically includes real estate taxes, building insurance, and maintenance (Thomson Reuters Practical Law, 2024).

Similarly, structuring the transfer of ownership as a share deal instead of an asset deal also exempts building owners from the Flanders renovation obligations. However, if there was an existing obligation to renovate, this obligation transfers with the company and the timeline to complete the renovations remains unchanged, despite any corporate restructuring or share deal (Linklaters, 2023).

Insufficient lead time and support for implementation

A study by the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors has pointed out that the current proposed timeline and trajectory for MEES in England and Wales are increasingly viewed as unrealistic by industry players, and there is lack of implementation mechanisms. As a result, there is a risk that up to 50% of commercial buildings could be stranded by 2035 if no further action is taken (RICS, 2024). Recently, the UK Government, via DESNZ, has pushed the interim target of achieving an EPC rating C for all new non-domestic lettings from 2027 to 2028 (Energy Advice Hub, 2024). However, MEES goal for the non-domestic building stock to achieve a minimum of EPC B rating by 2030 remains unchanged. DESNZ viewed that this amendment would allow a sufficient lead in time for landlords to prepare for the legislation to come into effect once a government response is published (Elmhurst Energy, 2023).

Furthermore, issues and inconsistencies with the financial incentives for energy efficiency improvement measures have also resulted in both building owners/landlords and tenants incurring unexpected upfront costs for heating upgrades. The Green Deal, for instance, was designed to facilitate heating upgrades in residential and commercial properties at no upfront cost. However, the policy was discontinued after about two years due to design flaws, such as restricting full funding to investments with high rates of return (Rosenow & Eyre, 2016). Currently, there is the Boiler Upgrade Scheme in place for domestic properties in England and Wales, offering subsidies of £7,500 for heat pumps and £5,000 for biomass boilers (Ofgem). However, it has been reported that building owners/landlords and tenants may still face out-of-pocket expenses since typical heat pump installations often exceed the subsidized amount, especially when considering the cost of installation and additional components (BBC, 2024). This is contrary to the initial MEES England and Wales policy design, which intended to avoid upfront costs and ensure no net costs to landlords (McAllister & Nase, 2019).

Potential conflicts with tenants

A study reported that MEES for England and Wales has created complications for landlords when it comes to upgrading heating systems (McAllister & Nase, 2019). The applicability of MEES is triggered by lease renewals, but if a building is continuously occupied by tenants, it may be challenging to find a suitable time window for these upgrades. Additionally, the study identified that tenants often resist the disruption and costs associated with heating system improvements.

Unlike MEES, which does not legally require tenants to comply with upgrade work, the renovation obligations in Flanders explicitly states that tenants must accept the disruption caused by energy renovation, even if tenancies are ongoing but the building ownership has changed (Vlaanderen, n.d.). Under the Belgian Federal Commercial Lease Act, if the landlord is required to perform urgent work during the lease, tenants must allow the work to proceed and cannot claim damages or seek a rent reduction unless the work exceeds 40 days (DLA Piper, 2024). Urgent work is defined as any work that must be done immediately and cannot wait until the lease ends without ‘detriment’ (AMS Advocaten), which may include financial implications for landlords if the work is not completed by the renovation deadline. Therefore, tenants typically must accept and cooperate with the landlord during renovation works unless both parties agree to different provisions in the lease contract.

The French Tertiary Decree can also impact the landlord-tenant relationship by including a clause establishing shared responsibilities between the two parties. The Decree mentions that tenants are responsible for reducing energy consumption through behavioural changes during building operation. However, the Decree does not clarify who is responsible for installing energy-efficient equipment or covering the costs of energy renovation work. Furthermore, in practice, tenants may be charged for all renovation costs, including energy upgrades, if leases are signed after the Pinel Law came into effect on January 1, 2015 (Soulier Avocats, 2014). For context, Pinel Law or Loi Pinel is a French regulation aimed at promoting investment in rental real estate. It offers tax reduction for investors who purchase or construct a new build property and commit to renting it out for a minimum of six years. There have been some changes to the law since 2022, such as the tax benefits being progressively reduced for eligible properties built between 2022 and 2024 (FrenchEntrée, 2023). The French government plans to end the Pinel Law by the end of 2024 (Brahin, 2023). This situation could lead to significant disputes between landlords and tenants if their responsibilities are not clearly defined in the lease contract. On the other hand, energy performance improvements will affect the rental value of the property, which will be a key consideration in lease negotiations at the end or renewal of the lease (Seban Avocats, 2023).

Connecting to a heat network

Workshops with housing developers and non-domestic building representatives, as part of research carried out in 2022 for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (now DESNZ), found that mandatory connection to heat networks for non-domestic buildings may be perceive as too ‘black and white’ (BEIS, 2022). Instead, workshop attendees suggested a zoning system must account for the complexity of businesses’ individual heating requirements and participants encouraged market-based solutions rather than mandating connections. They considered clear communication and information on heat networks to be an important step in supporting non-domestic building stakeholders.

In surveys, as part of the same research project, respondents stated that their business pays ‘a fair amount or a lot of attention to the costs of their building’ and 84% stated that it is ‘somewhat, moderately or very important for their business to have the ability to switch heating or hot water suppliers’.

In France, local authorities can classify heat network areas. The classification makes it mandatory within that area to connect any new buildings or building undergoing major renovation work if they have an output over 30kW. The law started as voluntary in 2018 and became mandatory in January 2022. There are exemptions to the obligation to connect, including if the heat network is operating at a low temperature that is incompatible to the needs of the building or if the characteristics of the building do not allow a connection (Construction 21, 2023).

Analysing the impact on non-domestic stakeholders

As part of this project, we have carried out desk research and interviews with subject matter experts to understand potential impacts of the HiB Bill proposals on non-domestic buildings. This has included exploring the impact on stakeholder groups, lease arrangements and building types. Interviewees were asked about the impact of a requirement to upgrade non-domestic buildings, and how the impact would vary depending on whether there is a sale trigger point or just a backstop date.

The stakeholders interviewed represented the following types of organisation:

- Law firms

- Real estate services and investment companies

- Registers of Scotland

- Federation of Small Businesses

As outlined in Section 4, there are two key lease arrangements in Scotland, FRI and IR, with FRI leases being the most common. There is a huge variation in the clauses that will exist within leases so it is not possible to know exactly how each building, and its stakeholders, will be impacted without reviewing the specific lease(s). For the purpose of this project, we have provided an illustration of the impact on four key scenarios to explore how key stakeholders are likely to be impacted in each.

Through the desk-based research and interviews it became apparent that the lease type would not be the key factor affecting the impact of this policy on different stakeholders. Key variables are the presence of a single or multiple tenants in the building and the clauses in the contract between the tenant(s) and the landlord. Therefore, the two scenarios explore options of FRI leases where the clauses allow for different levels of cost and responsibility to be passed onto the tenant, each of these scenarios broken down into two to explore the impact on single-let and a multi-let buildings. For IR leases, it will similarly depend on the clauses and tenants in the building and similar outcomes can be expected. In scenarios 1 & 3 where the building is upgraded whilst it is empty there is an assumption that the vacant period is within any relevant grace period or backstop date.

- Single-let building where the clauses in the existing contract do not allow the landlord to pass on the obligation for a heating improvement to the tenant. Therefore, there is less incentive for the landlord to upgrade the property with the tenants in-situ and the nature of the upgrade makes it challenging to do so. Therefore, the landlord waits until the end of the existing lease period to upgrade.

- Single-let building where the landlord is able to transfer some or all of the cost of the new heating system onto the tenant. Therefore, the landlord chooses to install upgrades while the tenant is in the property to allow them to recover more of the costs.

- Multi-let building where the clauses in the existing contract do not allow the landlord to pass on the costs for heating improvement to any tenants in the building. Therefore, there is less incentive for the landlord to upgrade the property with tenants in-situ Therefore, the landlord waits until either parts of the building or the whole building is empty.

- Multi-let building where the clauses in the existing contract allow the landlord to pass on the cost to tenants through the service charge. Therefore, the landlord upgrades the property with the tenants in-situ.

The challenges identified in the desk research and interviews can be grouped into three key themes. We have used these themes to provide an impact score for each:

- Cost

- Disruption

- Legal complications

Each of these scores have been given to both landlords and tenants, and also building management organisations for the cost impact.

In each of these scenarios, we have assumed the existing heating system is a polluting system and will need to be replaced with a clean heating system, with some changes to elements such as the pipework and heating controls also required. There will be scenarios where the heating system requires minimal upgrades to meet the policy requirements and therefore will be a simple installation that can be easily done without causing significant disruption. In these cases, the disruption and cost impact will be much lower. The legal complexity will still depend on the clauses in the contract but there is likely to be less pushback from the tenant as the cost and disruption is low.

Summary impact assessment (cost, disruption and legal)

Table 4 below provides a summary of the impact analysis across cost, disruption and legal implications to landlords, tenants and building management companies. The impact score and assessment in the section below is our analysis based on the findings from the interviews in addition to the desk-based research. In the sections below, further detail on the scoring and the nuances in each scenario is provided. A scoring key is provided below.

Table 3: Scoring key

|

Score |

Meaning |

|

1 |

Low / no negative impact |

|

2 |

Limited negative impact |

|

3 |

Medium negative impact |

|

4 |

High negative impact |

|

5 |

Very high negative impact |

To note, these figures provide an indication of the likely impacts on different lease arrangements but there is likely to be substantial variation within each lease type based on the clauses agreed between the tenant and the landlord. The interviewees presented varying views on the impact and responsibilities on different parties, particularly the responsibility for the landlord or tenants to cover the cost of the new heating system. This illustrates the complexity of introducing these requirements and reflects the confusion over responsibilities that been found in England and Wales when introducing the MEES requirements (RICS, 2023).

Table 4: Summary of impact assessment

|

Cost |

Disruption |

Legal | ||||

|

Owner / Landlord |

Tenant |

Building Management |

Owner / Landlord |

Tenant |

Owner | |

|

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost |

4 |

3 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

3 |

5 |

1 |

3 |

5 |

4 |

|

Multi-let: landlord responsible for cost |

5 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

2 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

Cost impact assessment

Table 5 below provides an impact score for owners, tenants and building management based on the cost they could incur due to a requirement to upgrade their heating system.

Table 5: Cost impact assessment

|

Owner / landlord |

Tenant |

Building Management | |

|

4 |

3 |

1 | |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

3 |

5 |

1 |

|

Multi-let: landlord responsible for cost |

5 |

4 |

1 |

|

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost |

2 |

5 |

1 |

We have provided insights on the impact on landlords and tenants in the sections below. Building management companies will not have a financial responsibility for the upgrades but they may have responsibility for delivering and coordinating the works. It is likely that if this requires more staffing they will charge a higher fee to the landlord. There may be more complexity for them managing tenants in a multi-let building

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: This scenario assumes the landlord waits until the building is empty to install the heating system. The landlord will pay for the full heating system and will lose out on rent while the building is empty as upgrades are taking place. They may be able to recover some costs for through charging higher rent to tenants after new heating system is installed.

Tenant: Directly incurs no cost of the heating system but has to move out at the end of the tenancy to allow works to be done. Additional cost of finding new working space and legal fees. New rents may also be higher due to landlords raising cost to cover this requirement. In addition, the new heating system may have higher running costs.

Further considerations:

- If the landlord is responsible for paying for and designing the new heating system there is less incentive to pick a system with lower running costs.

- If the new heating solution is a heat network the tenant may be responsible for higher costs and no ability to switch energy suppliers.

Single-let: costs passed onto the tenant

Owner / landlord: Responsibility to pay for some elements of upgrades (e.g. plant room). They are likely to incur legal fees to manage existing tenants.

Tenant: The tenant is required to pay for some or all of the new heating system.

Further considerations:

- If the requirement to upgrade is triggered by a building sale the tenant is likely to have no foresight of that and taking on any additional costs for a new heating system could be very challenging.

- If the new heating solution is a heat network the tenant may be responsible for higher costs and no ability to switch energy suppliers.

Multi-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: The landlord will pay for the full heating system and will lose out on rent while the building is empty as upgrades are taking place. With multiple tenants it takes longer to get the building fully occupied again, meaning they receive reduced rent. They may be able to recover some costs for through charging higher rent to tenants after new heating system is installed.

Tenant: Tenant directly incurs no cost of the heating system but has to move out at the end of the tenancy to allow works to be done. Additional cost of finding new working space and legal fees. New rents may also be higher due to landlords raising cost to cover this requirement. New heating system may have higher running costs.

Further considerations:

- It is likely to be challenging in many cases to agree responsibility of costs if the clauses in the contract are not clear

- If the new heating solution is a heat network the tenant may be responsible for higher costs and no ability to switch energy suppliers

Multi-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: Landlord passes on majority of cost obligation to tenant.

Tenant: Tenants pay for new system through the service charge. For tenants with longer leases they may be more accepting of this cost but likely tenants with shorter time left on their lease to accept this.

Further considerations:

- It is not clear how costs would be shared across multiple tenants with varying contract terms and different bargaining power.

- If the new heating solution is a heat network the tenant may be responsible for higher costs and no ability to switch energy suppliers

Disruption impact assessment

Table 6 below provides an impact score for owners, tenants and building management based on the disruption they could incur due to a requirement to upgrade their heating system.

Whilst we have provided an indicative score to give an understanding of the level of impact on different stakeholders there will be variety in every case. The level of disruption will vary significantly depending on the level of upgrade needed and type of business. Key factors in the level of disruption include:

- Size of retrofit project: For example, upgrading from a gas central heating system to a heat pump or connecting to a heat network would be a major retrofit project.

- Type of business: For example, if the property needs to be empty for one week this will be more of an issue to a shop (who will miss out on business) than an office (whose employees could work from home).

- Ability to provide back-up heating.

- Availability of workforce to deliver upgrades (e.g. there could be delays to the project if there are no skilled workforce available to carry out the works).

Table 6: Disruption impact assessment

|

Owner / landlord |

Tenant | |

|

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost |

4 |

3 |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

3 |

5 |

|

Multi-let: landlord responsible for cost |

5 |

5 |

|

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost |

4 |

5 |

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: Landlord responsible for installation of new system when the property is empty. Significant challenges to determine what heating system and find skilled workers to install quickly and minimise the time without tenants, and therefore without rent.

Tenant: Tenant may have planned to renew contract but will be removed from the property to allow upgrades to happen. There may be challenges finding new properties that haven’t got higher rent or likely to yet to be upgraded (and therefore at risk of requiring upgrades in future)

Single-let: costs passed onto the tenant

Owner / landlord: It will be very challenging for the landlord to agree with the tenant to install the new heating system while they are in the building.

Tenant: A new heating system (particularly if transitioning to a heat network or heat pump) will be extremely disruptive. Tenants may need to temporarily move out to allow the works to take place.

Further considerations: Even once a new system is in place it may cause disruption to the tenant as it may not meet the needs of their business as well as the old system as efficiently or cost effectively.

Multi-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: Tenants are likely to be at different points in their contract (e.g. one could have 12 years left in the building and one could have 2 years). It will be challenging for landlord to arrange for unoccupied period for upgrades.

Tenant: Tenant may have planned to renew contract but will be removed from the property to allow upgrades to happen. There may be challenges finding new properties that haven’t got higher rent or likely to yet to be upgraded (and therefore at risk of requiring upgrades in future).

Further considerations: Different tenants may have different heating requirements and new systems may not meet their needs.

Multi-let: landlord responsible for the cost

Owner / landlord: It will be very challenging for the landlord to agree with the tenant to install the new heating system while they are in the building

Tenant:

- A new heating system (particularly if transitioning to a heat network or heat pump) will be extremely disruptive. Tenants may need to temporarily move out to allow the works to take place.

- If there is a central heating system for the whole building, there is a risk that the new system does not work as well for some businesses

Further considerations: Even once a new system is in place it may cause disruption to the tenant as it may not meet the needs of their business as well as the old system (e.g. a business needing large volumes of hot water on demand).

Legal impact assessment

All parties will want to reduce the cost and disruption in their business so will aim to identify the relevant clauses in the contract that will prevent them taking on this cost or disruption. It is likely there will be cases where there is some ambiguity in the obligation with existing contracts which will add complexity. However, in other cases there will be clear responsibility and limited legal negotiations.

Table 7 provides an assessment of the legal impact on both the landlord and tenant.

Table 7: Legal impact assessment

|

Legal impact on owner / landlord and tenant arrangements | ||

|

Single-let: landlord responsible for the cost |

3 |

In a scenario where the requirement to upgrade is triggered by a sale there could be a challenge where the grace period is shorter than the current tenants existing lease period. Therefore, waiting for them to move out the property could cause the landlord not to comply with the obligation. |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

4 |

There are likely to be negotiations between landlord and tenant to agree rights around cost and disruption. |

|

Multi-let: landlord responsible for cost |

5 |

For some tenants, they will not easily be able to find an alternative space. For example, finding a new office space will be simpler than finding a new industrial space or retail space. |

|

Single-let: cost passed onto tenant |

5 |

Each tenant is likely to have some differences in their contract and differing time left on their contract. Reaching an agreement between landlord and all tenants will be very challenging. It is likely that tenants without much time left on their contract (e.g. 1 year) will be more resistant to paying for, and being disrupted by, a new system than a tenant with longer on their contract (e.g. 15 years). Included within a multi-let building will be areas which are communal and private. A heating system is likely to cover all areas of the building and therefore there may be situations where it is clear which parts are the responsibility of the landlord and tenant or between tenants. Cost sharing across multiple tenants would need to be negotiated and agreed How do the tenants agree on a type of low carbon heating which suits all of their needs / use cases? |

Key factors in the impact on different stakeholders

This section provides an illustration of the nuances within each scenario and the challenges associated with different arrangements. There were varying and uncertain views expressed from stakeholders about the impact of this policy on different parties but there was agreement that upgrading non-domestic buildings would be very challenging in many cases. The impact will vary depending on the type of building, the lease arrangement and the specific requirements and timeframe of the property (e.g. whether the requirement is triggered by a property sale or long lease and the length of the grace period).

Installing low carbon measures with tenants in-situ

As demonstrated in Table 8, if there are tenants in the building, and the clauses in the contract allow it, the landlord will want to pass on as much of the cost to the tenant as possible, either through their direct responsibility for parts of the building or through the service charge for communal areas. There will be some cases where the upgrade to low carbon heating is a simple installation that can easily be done without significant disruption to the tenants. However, many low carbon upgrades will be very disruptive to the tenant and in some cases will not be able to be delivered while the tenant is using the property, for example if converting to a heat pump or low temperature heat network which requires changes to the pipework in the building. The impact of this will vary depending on a number of factors, including the complexity of the work, and therefore the time needed for the upgrade, and the ability of the business to continue operating in this period.

Multi-let building leases

While both stakeholders in both single-let and multi-let buildings will encounter significant challenges complying with a requirement to upgrade their heating system, all law firm and real estate investment interviewees agreed that lease arrangements in multi-let buildings, is the more complicated scenario. One interviewee stated that “in multi-lets you may not have a time whereby all occupiers are at the end of their lease at the same point and therefore landlords may not have the opportunity to come in and make refurbishments”. If a landlord is responsible for carrying out the works, there will be significant challenges in delivering any upgrades whilst tenants are in the building. Many leases will have clauses preventing a landlord entering the tenants’ part of the building. For the landlord to arrange the upgrade with all tenants will be very complicated.

Additionally, as set out in Table 1 above the leases in the building are likely to vary in length and there may not be an obvious trigger point when the building is vacant.

Challenges associated with trigger of sale/long lease

The requirement to upgrade within a certain timeframe after property sale was a concern expressed by most interviewees. Upgrading a heating system will be a large project in many buildings and some interviewees argued that where possible the upgrade should be done at the most appropriate time in the building’s lifecycle, such as when a refurbishment is due.

If a trigger point is based on a purchase, or long lease change, this could cause significant challenges for the tenant. Tenants are unlikely to have any visibility or control over the sale of a property. If they do not know when a building is going to be sold, and the sale of the building leads them to either take on some cost of a new heating system or disruption to their business, this could be a significant challenge for their business. Without any foresight into when this may happen, they cannot budget for that cost. some interviewees commented that a two-year grace period would be far too short for many business tenants to find funding for a new heating system. One interviewee started the interview discussion by stating that the “trigger point is very important” and was a significant point of concern for them.

One interviewee suggested a two-track system for the grace periods. This would mean the party involved in the transaction would have a shorter grace period and tenants, if they have responsibility, would have a longer grace period. This would support tenants where they were not aware the sale was coming up and have not been able to build it into their business plan.

Others suggested that a policy deadline, without a sale or long lease trigger, would be far easier for building stakeholders to comply with and would allow stakeholders to appropriately plan for the upgrades. This would allow obligated parties to build trigger points, such as vacant possession and refurbishment cycles, into their retrofit plan.

Shortages of skilled workers

Another challenge for the party upgrading the system will be identifying the appropriate heating system and finding the skilled workers to deliver it. One interviewee pointed out that if there is a requirement for many buildings to upgrade their systems in the next few years there is unlikely to be sufficient skilled capacity in place to deliver this. There needs to be sufficient investment in the low carbon heating sector and its skilled workforce, and the design of the regulation needs to consider situations where parties are looking to upgrade their heating but cannot meet specified timelines due to workforce shortages. Without this there is likely to be significant delays to heating upgrades which would heighten the impact on both landlords and tenants.

Conflicting requirements

Assuming the obligation is set on the landlord, the requirement to improve a heating system could conflict with other requirements in their contract with the tenant. Many retrofit projects will be very disruptive to tenants and potentially stop them from being able to operate for a period of time. For example, the Property Standardisation Group (PSG)’s model ‘Commercial Lease of Part of a Building’ (Property Standardisation Group, 2024) includes the following clauses for the landlord to comply with:

- “Cause as little interference to the Tenant’s business as reasonably practicable”